Rarely does a major piano competition go by than we see social criticisms of the results. Check out recent discussions about the 2017 Rubinstein, the 2015 Leeds, and the 2015 Tchaikovsky. In the first and last case, we even had jury member Peter Donohoe wade (with some disdain) into the commentary (see, in particular, his exchanges in the Rubinstein link). Someone is always going to be upset about the winner’s style of playing, will wax poetically about the insufficient jury’s decision to choose a ‘consensus’ candidate instead of another finalist, the individualist, who some loved and others hated.

I’ll admit to having these criticisms myself. I thoroughly loved that the 2015 Tchaikovsky competition discovered Lucas Debargue, and while I was upset he didn’t win, he has clearly won himself an audience and likely a successful career. I wasn’t excited by either of the 2009 Cliburn winners, but I predicted in the first round of the 2013 contest that Vadym Kholodenko would be the winner. I never thought much of Allesandro Deljavan, the competitor many loved and thought it a travesty when he was eliminated. Before the medal announcement, I also rightly predicted the 2nd and 3rd place winners. With the 3 medalists, I thought the jury found the perfect balance between virtuosity, musicianship and unique choice of repertoire that wouldn’t turn off the die-hard or casual classical fan, and an individuality, an intentionality to each performer’s pianism. This spring appears to be the season of major competitions with the Rubinstein and Montreal just completed, running virtually at the same time, then the Cliburn a few weeks later. Due to professional commitments I didn’t listen to much of either of the former two. But I’ve listened to the winners and at least one medalist at each. To be candid-I wasn't excited by the winner in the Rubinstein. If we check out his repertoire through the solo rounds, we see Scarlatti, Beethoven, Mozart, Chopin and Rachmaninoff (the standard fare, though at least with underplayed sonatas from the first three, and a diverse batch of Etudes from the latter), and some interesting Szymanowski to go along with the imposed contemporary piece. But I loved the winner of the Montreal competition, Zoltan Fejervari. As one of my friends said, “ …everything he played is standard repertoire but the combined program is so unique and really sets him apart.” His solo repertoire included Bach, Beethoven, Ligeti, Scriabin, Bartok, Janaceck and Schumann. Most of his choices were of lesser heard selections from each composer. It seemed clear to me from his programming and his manner of playing that Fejervari wasn’t competing to fit a ‘winner’s’ mold, instead, he presented his own artistry in a take it or leave it way. One of the riskiest choices a competitor in a competition makes is choosing their final concerto. How often do we see Rachmaninov’s or Prokofiev’s second or third concerto, or the Tchaikovsky first? The Rubinstein finalists all happened to make the safest choices possible: 3 played Rachmaninov 3rd, 3 Prokofiev’s 3rd. I say safe as in, you have the best chance to show off your mastery of the instrument. But Fejervari played Bartok’s 3rd in the finals—not an easy piece, but he had the added task of convincing the jury that this piece was worth competing with against the ‘war-horses’. (The last winner of the Montreal Competition won with Beethoven 4, an equally risky choice.) I’ve been skeptical of the propensity to see many of the same pianists sitting on the juries to multiple major competitions each year. I don’t blame jury members for accepting invitations, but why do competition boards continue to ask from the same pool of artists? If the goal is to find a young artist that stands out among the rest, you don't want the same crowd choosing that winner; inevitably the same jury members will choose the same kind of pianist. The issue of jury member’s students competing is another one, fraught with questions of correlation and causation along with competition rules that I’d prefer not to get into. It’s covered quite well in this article in response to Veda Kaplinsky and previous Cliburn competitions. The Cliburn has attempted to avoid these issues entirely this year. In the press release first announcing the 2017 jury and rules for application, they made note that only one of the competition jury had ever served before, and that the screening jury competition jury was comprised of entirely different people. They further made a brave attempt to avoid bringing teachers on to judge, focusing on (recently) retired professors and several artists who exclusively perform. From what I can tell, they were largely successful in avoiding student and teacher pairings among competitors and jury. Their focus clearly was on establishing a jury with a wide variety of unique, intentional artists and I expect that the eventual medalists will reflect this. I think it shows in the competitors chosen for the Cliburn, starting this week. They are from all over the world, and there is very little repetition among their place or professor of study. And their repertoire! Yes, among the concertos, we see the same warhorses: 4 with Prokofiev 2, 5 with Prokofiev 3. 5 with Rachmaninoff 3, and 7 with Tchaikovsky. But, 0 playing Rach 2! Among solo repertoire, only 3 offer Stravinsky’s Petrushka, and 4 Ravel’s Gaspard de la Nuit, two pieces I thought everyone tried to do at the last iteration. What about what’s novel? A few offer Beethoven’s 4th concerto, or Liszt 2nd, and each of Chopin’s are the ‘grand concerto’ choice of one competitor. There’s a few solo Messiaen offerings, Clementi, C.P.E Bach, a few Schubert Impromptu sets, and a variety of J.S. Bach, and several people offering contemporary composers such as Carter, Ades, Takemitsu, Corigliano, Rzewski and Auerbach, in addition to the imposed piece by Marc-Andre Hamelin. There are many examples of someone playing a less virtuosic or less known piece from a well known composer, say Scriabin (10th Sonata), Brahms (Op. 118), Prokofiev (4 etudes), Shostakovich (1st Sonata), Debussy (Reverie). And the sheer art of programming. So many competitors programs work against your expected programming of romantic repertoire with a nod to something a little more conservative, in the best ways possible. Two examples I’ll point you to are Luigi Carroccia’s entire program, and Dasol Kim’s Semifinal recital. So-I’m optimistic and excited to be bathed in piano playing. I will be posting reports every two days or so. I hope to not fall into the trap of being a ‘back-seat’ jury. I’m hoping to be so intrigued by all kinds of great piano playing that I can just wax poetically with optimistic fervor. I’m sure I’ll have my favorites and my least favorites, but more than anything, I expect to be intrigued, excited and inspired. Hopefully I can share that with you! A lot of studying the piano is learning to copy, from our youngest years through at least until completing undergraduate education. Initially, this isn’t a bad thing. We need models to learn:

But there comes a time that we want to move away from copying. Until we do, we generally only function as accidental, or perhaps unintentional, pianists. We’ve done everything by chance, regurgitating what we’ve learned instead of processing and adding value to everything we’ve been taught. Sometimes when we think we’ve gone off on our own, we haven’t actually done so. I’ve argued that the act of performing is at least as important as the texts on which our performances are derived. I believe our ears are easily manipulated by what we hear and most of our performance decisions are not truly our own; see case studies in Beethoven and Liszt. And so I’d like to suggest embracing what I have decided to call 'intentional pianism'. What makes a great pianist stand out? Our favorite pianists have at once a pianistic voice that is all their own, that sounds completely familiar, and simultaneously keeps us thinking and guessing. They’ve studied all the rules but have commanded the authority to break them. They have a sort of intentionality to the way they play music. All this is not to suggest that intentional piano playing is limited to the great masters. Some of my absolute favorite musical memories are from pianists who are not famous to the general classical music population. Some of the most distinctive performances I’ve seen were by students who brought an energetic commitment rare among artists, others are from professional artists who have sought their own career path, whether to pursue unique repertoire or venues for their performances. Anyone can play with intentionality. Nor do I want to suggest that our educational system is failing students. I’ve benefited from studying with an incredible, diverse group of piano teachers, all of whom are brilliant, and largely fall into the category of a ‘traditional’ piano teacher. And there’s nothing wrong with role of traditional piano teacher, in fact, traditions are essential. But to step out as performers with a personal intentionality, we need to use traditions as a stepping stone, not an end in themselves. Our professors in lessons and classes only have so much time to help us reach the level of being a unique artist. My goal with this blog and other future endeavors is to supplement the great teaching that goes on in piano lessons and schools of music. I believe some of the keys to being intentional include:

With this blog, most of all, I hope to outline how one can become a truly independent, a truly intentional pianist. Over the course of this next year, I’m going to present 5 blog series along with several standalone posts. First will be Extraordinary Recordings, a series studying several of my personal favorite performances on record, focusing on what makes the performer so unique. This will be, in a sense, a series of 9 case studies on pianistic intentions. Simultaneously, I will report on my viewing of the Cliburn Piano Competition, my favorite performances as well as thoughts on the repertoire chosen, and nature of competitions in general. What better way to ruminate on the state of intentionality than by studying this competition of world-class, young talent? Later on, with the hope of inspiring some summer reading, I will release a series of posts on Influential Books. Some of these will be explicitly musical, but several will be from outside the musical world. In the fall, I will be ruminating on the Coexistence of Contemporary and Traditional Classical Music. This will be in preparation for a project that I’m very excited about, which I will announce later in the summer. Finally to end the year, I will discuss my views on Performance Practice, especially focusing on my work studying the amazing pianist Ervin Nyiregyhazi. I hope you’re as excited about this journey as I am. Please subscribe to my e-mail list to the right, as I would love to keep you apprised as each new series is rolled out, as well as my projects as a performer.

A change of pace from the Messiaen...

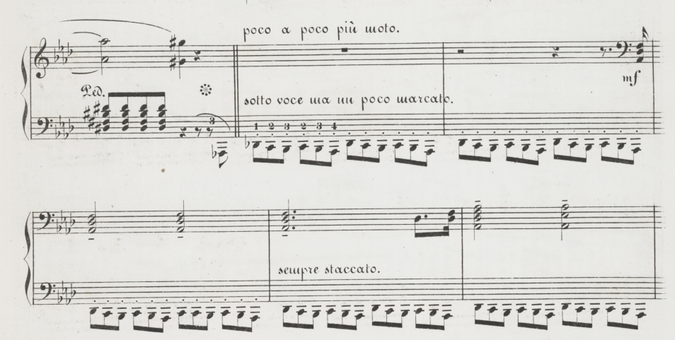

I have sat on this recording for almost a year and a half now. In general, I was not happy with this recording session and only had a couple movements of Mozart cleaned up to actually share publicly. But I’ve continued to think about this Franz Liszt run. It is messy in the beginning with a couple memory lapses but generally stays on track and presents how I’ve heard this piece in my head. But there is another reason I’ve always been hesitant to widely share my performances of this piece. I drastically depart from the standard performance practice in one notable area. Funérailles is famous for the middle section fanfare, the military parade which, as the route passes by the listener, the pianist explodes the thunderous bass ostinato with octaves. It’s virtuosic and may or may not reference Chopin’s famous A-flat Polonaise. Here’s the beginning of the section, from the first edition: Notice the tempo marking: poco a poco piú moto, or, ‘little by little more motion’ from the last tempo indication, which was adagio, in the very beginning. Other editions, including Henle’s Urtext, and editions by Emil von Sauer and Liszt student Jose Vianna da Motta agree. And YET no one plays it like this. At the beginning of this section, the second measure in the excerpt above, performers always take a new, fast, tempo. I’ve never understood this. Franz Liszt clearly marks a new tempo (Allegro energico assai) only at the climax of this section, and continues to reinforce the poco a poco piú moto until that point is reached. But performers always begin this section very fast. Are they afraid that they will not be fast enough by the time octaves are introduced and be accused of lackluster octave technique? Practice pacing yourself. You can start slowly but get to a tempo to leave no doubt in your abilities. You run the risk of the opposite problem: starting fast, and trying to get faster so that your octaves are doomed to fail. Even Horowitz succumbed to this extravagant failure and had to drastically cut the tempo back at the climax of the section. My performance of the military march here is an accurate depiction of this section, I think, and the effect of movement, the tension of the unyielding ostinato, and the pride of the moment is accentuated if this section begins adagio. It makes for a strong musical choice, but I have yet to find anyone to actually make this observation, whether in writing or in performance. Particularly listen to 7:00-9:15. The military march section begins at 7:25, the octaves at 8:30, and the Allegro energico assai at 8:50. What do you think? Give it a couple listens then tell me if you're convinced, or if you find the sudden tempo change a better choice. I'd love to hear from you!

Who doesn't love a beautiful sunrise and sunset? Natural beauty that reminds us of the simple things in life.

How does a sunrise and a sunset sound in music? Olivier Messiaen, not just a lover of birds, also sought to show the sun rising and the sun setting in music in his piece that I'm preparing: La Rousserolle Effarvatte. Here's the audioblog #2 to prime your listening!

Here's a post especially for my students!

I'm preparing a BIG piece for performance in a few weeks at the Toledo Museum of Art, part of a marathon concert of 10 pianists playing Messiaen's Catalogue d'Oiseaux. I'm playing the 7th of 13 pieces: La Rousserolle Effarvatte. Here's a link to the event This is difficult music to listen to, especially if you've never listened to contemporary music! Even if you have, this piece jumps around a lot and it's hard to find a through-narrative. What should you listen for? Yet, I think this piece is truly beautiful. As a result, I decided to create a series of audio/video posts to aide in listening. Here's the first in the series where I discuss some general background to the composer and the piece (recorded with real live birds in the background!), and two specific bird calls that Messiaen uses:  My wife and I bought a house almost a year ago, a home we absolutely love. It’s old, well maintained and full of character. We were ‘sold’ as soon as we saw it. One misgiving we had was the backyard-the garden area was very over grown with tall weeds, and piles of yard waste. So my Dad came out one weekend to help me clean it up. We forgot to take a ‘before’ picture, but here’s an ‘after’ picture of our beautification project: I share this image because I think it is decidedly NOT beautiful! Grass has been torn up, we collected piles of wood, tomato plant cages, the garden boxes were rotting and falling apart, we found out our fence was not as steady as we’d thought, and the “garden” is still weedy and needs some good working-through before it will grow our preferred vegetation properly. But it IS much more beautiful than it was. I think this is a great analogy for my general practicing philosophy. I’d bet many of my students don’t take to my practice suggestions easily, and I can see why. I often ask them to distort what is on the page. Whether it’s practicing in rhythms, blocking, changing dynamics or articulation, the fact remains: We have to make something ugly before it’s going to sound beautiful. I’ve also used the analogy with my students of baking a cake. Batter is not the same thing as cake, its texture is off, the taste is not quite right; but we know that batter can become cake. We mix ingredients together but still have to bake it. We can never start with just cake. In my practice philosophy, practicing is mixing notes, articulations, phrasing, dynamics and rubato together using different practice techniques to create something akin to batter. Our cognitive processes then bakes it to create something tasty for our ears. Here’s a video of me learning a new piece: the Prelude in Bb major from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1. The first time around I utilize two techniques to reinforce the notes:

|

"Modern performers seem to regard their performances as texts rather than acts, and to prepare for them with the same goal as present-day textual editors: to clear away accretions. Not that this is not a laudable and necessary step; but what is an ultimate step for an editor should be only a first step for a performer, as the very temporal relationship between the functions of editing and performing already suggests." -Richard Taruskin, Text and Act Archives

March 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed