This piece can easily devolve into banging in the repeated left hand chords and unmelodic thumping in the right hand repeated notes. There is not a lot of melody, especially considering the amount of repeated E’s in the first phrase. The pianist’s challenge is to make this piece angsty and musical.

Reisenberg does this by leading to beat 3 in measures 1 and 3. This slight crescendo to and decrescendo from the beat creates a nice phrase, so the DNA of Mozart’s theme-the repeated notes-is not played like an apology, yet it doesn’t sound pedantic. Not that the second theme is much more melodic. Is the melody in the right hand filigree or the left hand chords? For Reisenberg, the answer is the latter, but her left hand is still phrased with very precise shaping and rhythmic cut-offs. This is very string-like playing. The left hand continues to dominate when it splits into two-part polyphony, but the real magic is in the right hand. Even though it’s subordinate, this is some of the most lyrical playing for seemingly “filler” notes. How many times have you heard these 16th notes played completely rhythmically? Some people would say that every note is pearly, but I’m not really sure what that means. To me, her fast notes seem to float out of the piano, she’s playing with a beautiful, light, and even tone, yet it’s as if there’s no bottom of the keybed, no percussive beginning to any one tone. I have to say a few words about Reisenberg’s development section: The drama is unleashed here. Mozart has undertaken a really nifty compositional trick. We hear the first theme in C major, elliding with the ending tonality of the exposition. He fakes a modulation to F major/minor, a perfectly natural progression, but in the sixth measure of this section, confuses the eye by replacing Db with the enharmonic C#. This makes no difference to the listener, but it’s a nifty trick to those following the score, signalling that something is up harmonically. In measure seven, we begin a downward cascade of broken chords on the dominant 7th of F, but in the next measure, rewrites that enharmonically as a German Augmented 6th chord so that we land in measure nine in B major. This key ‘splits the difference’ between the key we start in, a minor, and the relative major, C Major. The harmony isn’t stable in this new key for long, but it’s a noteworthy achievement that we ended up here at all. What Mozart was never great with is pulling apart his themes. He didn’t need to, he could create drama with a new melody, or with these tricky slights-of-hand. Not coincidentally, the left hand lives in a range much lower than it has inhabited thus far in the piece, in a stormy pattern that’s new too. Meanwhile the right hand has some biting dissonances. While Nadia Reisenberg perhaps kept the demonic powers at bay in the exposition, they are unleashed here. The bass booms, and while I’d have preferred that she not shy away from the right hand dissonances, she tracks the dotted rhythm through the entire left hand, creating a gnarly web of melody. When the first theme comes back briefly in A major, she makes no qualms about pounding here, while not hammering. As we land on the dominant to prepare for the return to a minor, she shows off the jumps and trills of the left hand very clearly. All of these elements make the Development section come alive. It’s hard to find the right words to describe the magic that is the 2nd movement of this Sonata in Reisenberg’s hands. Certainly, I don’t dare track moment by moment pianistic tools that she uses. This is beautiful playing, which has the delicacy that so many people crave in Mozart playing, but still amply phrased and melodies differentiated with clear articulation. A visual inspection of the score suggests a busy sounding movement: plenty of articulation, phrasing, rhythmic variety and accompanimental vitality. All of these differentiations are present, yet the sound of the music is simple, straightforward and natural. The finale is more agitated than angsty. Generally I’m happy with the balance she strikes between the hands. I think Mozart creates the illusion of independent hands, each hand with its own rhythmic ostinato and melodic shape, that line up for brief moments at cadences, when the left hand has quarter notes. I think a little more left hand would have made this compositional device more apparent, and the moments of coordination between the happens ironically jarring. But, when the hands flip ostinatos for the B-section in e minor, Reisenberg’s voicing is so mysterious and the interaction between the hands so nervous, that this oddly mono-themed Rondo is a great success. Bonus: Attached to the playlist is another pianist who recorded this piece but no other Mozart Sonata--Dinu Lipatti.

convince everybody, and I dare say that my approach to the music will evolve over the next two years.

To begin with, though, I want to listen to a Mozart performer who I love. Walter Klein was not someone I knew, actually. As I started to collect lists of pianists who had recorded complete Mozart Piano Sonatas, his name came up and I started listening, and was hooked. There is so much in his approach to Mozart that I admire and want to recreate in my own way. His Mozart is full of extroverted characters, obvious phrasing, and colorful textures. To get a sense of this, I thought I would focus on the Sonata which I'm learning this month: #1, K 279 in C Major. You can hear nearly everything that I love in Klein's playing in the first few lines:

Overall, the thing I like about Walter Klein's Mozart playing is that he doesn't aim for delicate consistency. Many pianists underplay the variety that is in Mozart's scores, like they're apologizing. Klein does not. The first measure of the last system on the second page is quirky, the grace notes snappy and tempo rushing, before he returns to a melodic texture. Everything has shape and articulation, and those shapes are not even, smooth and rounded. The Development of the first movement does not have quite the variety I'd have expected. The sequential elements are often played with the same momentum, rather than each measure phrased internally, as well as having a specific role in the entire sequential shape. But perhaps this is intentional; he's letting the harmonies speak for themselves. It's like this Development section is no-man's-land, harmonic anarchy, and such phrasing would be out of place without a tonal hierarchy. After all, he makes much of the harmonic differences in the recapitulation, where even in the first theme (bottom of the 3rd page), Mozart is making creative changes. I've always found the second movement of this Sonata to be very awkward. The fortes and pianos seem rather arbitrarily placed (i.e. 3rd system, page 9), and many sections seem to disregard the time signature entirely (i.e. last two systems of page 9). But the phrasing taken by Klein makes the movement make sense. Nothing is very extreme here, the dynamics, nor the rubato. But he uses enough create phrases that have internal logic, and thus, the whole movement seems to make sense. The finale begins with a typical 4-measure phrase. The second phrase begins with the same thematic material, but ends up as a 6-measure phrase. Klein makes this phrase sound normal by playing M. 7-8 exactly the same, rather than cheapening the repeated measure with hackneyed trick like the echo effect. M. 11-18, to contrast, is a typical 8 measure phrase, except it sounds uneven: Mozart fills these measures with nearly sequential material, except he always changes something: compare M. 13 and M. 15. Or take M. 12 and M. 14, which are sequential, vs. M. 16 which begins the same, but takes a new turn. In these instances, Klein plays up the subtle melodic shifts so that this typical phrase seems asymmetrical. Because his left hand is prominent, the extra quarter note on beat 2 of M. 16 makes the shifty composing unmistakable. Ignore left hands at your own peril! Consider Klein's treatment of the repeated note motive in the second theme: measures 23, 25 and 27 each have repeated notes but each instance is treated differently in terms of dynamic and rhythmic drive. Nothing is monotonous, even though it looks monotonous on the page. This, in short, is what I love about Walter Klein's Mozart playing. It's full of vitality and variety, and perfectly encapsulates the operatic elements that I wrote about on August 6th. Any music teacher worth their salt, who requires their student to make musical goals, knows to push their students towards realistic goal setting. That's not to say that a student shouldn't have a goal of "playing at Carnegie Hall", or "win the Cliburn Competition". But in order to achieve these goals, we need to formulate a series of interim goals.

The deeper you go in creating these short-term landmarks, the further you're actually getting from making goals, and the closer you are to making systems. I'm a big fan of scheduling my time, and acting in a consistent manner day to day. I wrote about aspects of my schedule when I spoke about my morning routine, and matching activities up with energy schedules. James Clear expands on this idea in an article about the benefits that systems have over goals. He suggests that if a coach of a sports team focusses on the systems built and refined in daily practices, inevitably is going to have greater success over the course of a season, than a coach focussed on winning a championship at the end of the season. If a championship is unattainable without the day to day systems in place anyway, why not put all energy and expertise into perfecting the system. Clear uses his own writing as an example. He set to a system of writing new articles every Monday and Thursday. Over the course of the year, he had produced a volume of work equivalent to 2 books. But if he had started that year with the plan to write 2 books, so many questions and unknowns would have gotten in the way: what should the book be about?, how should it be structured?, what sources should I draw on?...This is only off the top of my head. I spoke about something similar to this in a post called Dangerous Goals. James Clear's article adds elements to the discoveries I made there. Particularly, his second reason to focus on systems rather than goals. One critique that may be made about focussing on short-term systems rather than long-term goals, is that if we have no 'eye on the prize', we won't work towards anything in particular. But his point is that once we attain a quantifiable goal, we can easily lapse into passivity, perhaps regressing on the skills that took us to our goal. If we can't identify and replicate the systems that led to an achievement, even a new goal is like starting from scratch. Setting goals and working towards them is like trying to tell the future. We can't turn ourselves into something we're not. What we can do is start with an acknowledgement of our strengths and weaknesses, and work on systems, habits and schedules, that utilize our strengths. New skills will emerge, new habits formed, and inevitably we are capable of producing much greater work than ever before. So before you worry about visualizing a performance goal far off in the future (even six months is too far away), focus on your practicing. How is your practice system working out for you? How are your day to day routines supporting that system? Are you spending enough time practicing? Are you spending your practice time efficiently? Are you strengthening these artistic systems with personal growth, social time and paying attention to your physical health? Most of us would agree that the best piano playing has a certain spark of intuitiveness, spontaneity that could not be planned. Don't worry too much about planning your playing in the future. Plan your day, plan your work habits, and you might be surprised by the artistry that comes out.

I thought that a good summer project would be to revisit some old performances of mine. The oldest recordings of myself that I know to be in existence are from my second year of my undergraduate studies. I haven't found the CD of that session, but I'm sure it's somewhere in my home. I do have my junior and senior recitals, plus several other recordings from my undergraduate years, not to mention all recitals I've done since, and non-recital sessions of other works too. I'm lucky that I've made sure to get decent recordings of almost all major repertoire i've learned.

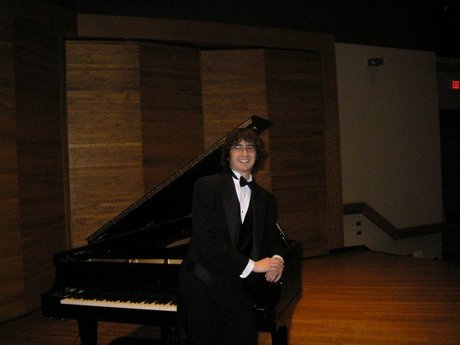

My memory would tell me that my piano playing back in the day was awful. I've improved technically since then, and clearly I had no idea how to listen to my own playing, interpret music correctly, or practice for strong, individual performances. As I listen back, I was actually quite wrong. I don't hate my playing from my late teens and early twenties. I hear problems in it, but I also hear an individualistic artistry which I recognize as an early version of my playing today. So I thought I'd share some old personal recordings and comment on them. First up is my Junior recital from January 19, 2007. This was my first full recital program ever, including Bach's Prelude and Fugue in D, WTC II, de Falla's The Miller's Dance, a couple Debussy Preludes, Morel's 2nd Study in Sonority, (maybe something else?) along with this Haydn Sonata. This date is the only time I ever wore a tux with tails, rented for the occasion, and for some reason, I thought so much hair was a good idea.

that one of my biggest issues was a tight hand and wrist, likely due to under utilized finger position, and poorly integrating all of my upper limbs. You can also hear it in the scalar passages like M. 36-37.

Some of the musicality is naive. You can count out all of the fermatas, they're far too unoriginal and ill-contrived. I would like to hear more detail in the articulations, especially a closer attention to slurs. A lot of "hits" are the exact same strength, i.e. M. 74, 76. But on the good side, I do back off for M. 78 to create a nice little line. There are other moments where I listen and match the tension and release of a line well, say M. 60-61 I really like how I listen to the ends of phrases; M. 4-5 and M. 6-7 make a nice pair, and M. 10 captures the confusion of landing on this strange chord really well. Overall, it sounds like I do get the jocular character of this piece quite well. I don't have all the tools to execute it yet, but I do hear something in my playing that I like, and I'm grateful that I had great teachers who heard it as well. I recently finished reading Anton Rubinstein: A Life in Music, by Philip Taylor. I had been eager to become more familiar with the life of Anton Rubinstein (not the better known, more recent pianist, Artur Rubinstein). Rubinstein is today known as a gargantuan pianist from the latter half of the 19th century, a contemporary of Liszt, and epitome of the Grand Romantic Artist. Many people have compared my beloved Nyiregyhazi to Anton Rubinstein: the huge romantic gestures, passionate performances full of equal parts enthralling personality and wrong notes.

In the end, Taylor's biography focussed less on pianistic aspects of Rubinstein's career. In fact, more insight into his playing can be found in the occasional mention of his work in After the Golden Age. There was some insight into his general artistic vision, and his dedication to performing. Across many months in 1872 and 1873, he performed over 200 concerts in the USA, including one stop very close to my current home, performing in Toledo, Ohio (I want to see if there is any record of this event locally). The book did emphasize his work as a composer, more than that of a performer. This was intriguing. I suppose I realized that he had written a lot of music, but I had only really heard his 4th piano concerto, and then, not in a professional setting. In fact, Anton Rubinstein seemed to regard himself as more of a composer than performer (similar, again, to Nyiregyhazi). He wrote over a dozen operas, several symphonies, an abundance of chamber music, lieder and a tremendous amount of piano in the form of concertos, sonatas, variations and character pieces. I've been looking at a lot of his music and listening to some. It seems fair that his output here has been forgotten some. It is rather conventional, and dare I say derivative of Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Schubert, with a few certain Russian touches. Not that there's a lot that is bad but given when he wrote, history was ready to give posterity to composers doing something more new. Some of it is very beautiful. As I write this, I'm listening to his Ocean Symphony for the first time. There are many beautiful melodies and gorgeous climaxes. He seems to understand writing for the orchestra very well as all sections are utilized in turn, and he writes quite a bit of polyphony. He seems to use form well to create drama and arch. But none of this is anything Beethoven hadn't done. I may learn a few piano pieces, perhaps to build a repertoire of encore pieces. I think it's most interesting to observe how much history can change our perception of artists. Perhaps if Anton Rubinstein had been alive during Beethoven's time, we'd speak of him as a giant, and Beethoven as a side character. Perhaps if Anton had been alive 20 years later and been recorded, biographies of his life would focus much more on his pianism. As it is, it's difficult to say a lot, other than report on reviews and accounts of his recitals. I wonder what it would have been like to hear him play, but for now, we must focus simply on his legacy as heard through his student, Josef Hofmann. Daniel Hsu happened to be about an hour away this past Sunday afternoon, at a concert hall I'd never seen before, in Findlay, Ohio. Beautiful hall and beautiful Bosendorfer piano. Daniel Hsu was my favorite Cliburn competitor last spring so I had to make the trip.

I still loved his playing these many months later, probably more than before. I was rereading some of my comments about him (see the rest of the Cliburn Competition Reports categories) and during the finals, I commented that it was as if he was playing the premiere of the Tchaikovsky concerto. His playing just has so much freshness but also naturalness.

My favorite had to be the Chaconne. It sounded more like a set of variations than I'm used to hearing, and that's a very good thing. Every single variation felt like an original composition with it's own unique voicing, subtleties of rubato. But it still held together and was clearly a single narrative. I've rarely ever heard the piano sound so much like an organ: layers of sound all emanating from the same source (I say this to differentiate from sounding 'orchestral' at the piano), but beautiful layers that were phrased individually and as a whole. He had some beautiful things elsewhere, of course. I was particularly drawn to lyrical melodies in the opening of the Chopin Fantasy. Where Chopin added a countermelodic harmony in the right hand, Hsu voiced them so subtly as just a tinge of color, instead of a full fledged second voice. I've been teaching about spectral music in both my piano repertoire class and with a private student, and specifically how these composers seek to alter our perception of the piano's timbre by specifically voicing complex, dissonant chords. It is a remarkable affect that does work, and Hsu seemed to capture an element of that: not letting the countermelody compete with the principle one. I found him focusing a little too much on the "dance" side of Chopin's famous 'concert-dance': his agogic accents were a little redundant for me. But overall his playing is imaginative, clean and energetic. Pictures sounded nowhere near its 30-minute length, and everything from the most bombastic to the most simple was given a thorough, thoughtful musical treatment. On March 23rd, I had the pleasure of seeing a recital by Joel Schoenhals, a pianist I’ve happily gotten to know this year. He’s embarked on a couple remarkable projects: performing all 32 Beethoven Sonatas in 8 programs over 4 years, and now the Bach Partitas and Brahms short pieces on 4 programs over 2 years. This concert was the last of that latter series.

I’d encourage you to check out the write ups that he has linked on his website about learning the Beethoven cycle (here and here). I love his dedication to the music and sharing it in both intimate and large environments. I also appreciate that he has focused on presenting complete and unedited performances of these concerts online. He sure doesn’t make many mistakes-whatever that term even means!-but the musicality and personality from doing it live is so engaging. I’ve never done studio recordings where every mistake can be rerecorded and spliced in, but I love the magic, the humanness of live performances. Check out the back catalogue of all of his recitals. What I love about Joel’s playing is that I’m always drawn in to what he’s doing that it never occurs to me to question or criticize his playing. I’m not actively thinking about reviewing or analyzing his playing as a musician myself. There’s something in his playing that invites trust in the work that he’s done and the performance journey that we’re on together. The music exists and for whatever period of time that he’s playing, it needn’t exist any other way. This was especially evident in the Brahms Ab Waltz that he played as an encore. You can check out his performance of the whole set here.

Years later and I love all kinds of contemporary music, and I've listened to Dawn Upshaw singing all kinds of things, and I've discovered this incredible pianist Gilbert Kalish who has done so much for legitimizing modern music through a historical context. Last night, I was able to hear these two iconic artists together in recital.

I have been unable to put much on my blog the last several months, but given that this week I have 3 marvelous concerts I get to go to, and my performing obligations are winding down for the year, I wanted to reflect on some of this music that i'm hearing. I'm less interested in giving concert reviews, than turn to some short-form thoughts and impressions from these performances. Rarely will I ever get to hear such remarkable artists live. The communicative effort of both Dawn Upshaw and Gilbert Kalish was clear from the very first notes either of them gave in the recital. Their collaborative partnership is clearly affectionate and respectful. I was explaining to my Dad-who accompanied me-what it was that made someone like Gilbert Kalish a better pianist than me. It seemed that the best thing I could suggest was that he has such wisdom in his playing. He's able to communicate his interpretation so clearly and so naturally, that I feel no need to consider any other interpretive choices. I could fully entrust his musical decisions. I don't know how much of this comes from someone who has performed, recorded and taught as much as he has, and how much of it he had when he was my age, but I can only hope to gain such wisdom as I continue to work. Dawn Upshaw...Well, it was a dream to hear her voice live. I'm amazed at her clear language: She sang (and memorized!) a set of songs by Bartok, and between her diction and acting, I might have convinced myself that I understood Hungarian, were I not following the original and translated poetry in the program. Like Kalish, the musicality and poetry are so present. She rarely had to use her full voice in this program, but that didn't mean every note wasn't stunning and expressive. For all our talk as pianists of having a 'singing tone', she was able to utilize such direct softness in her tone, which still filled the room. In light of my last couple of posts about listening and recordings, I thought I would point you towards this interesting article I had on my 'to read' list for several months, that just happened to fit the subject perfectly. It's called "Learning from Listening" and the author holds some of the same opinions I do, and some differing ones. Taken as a whole, I thought it would be worth sharing several excerpts, annotated with some of my own commentary. There are many benefits in listening to the repertoire you are working on, on disc and in concert, as well as “listening around” the music – works from the same period by the same composer, and works by his/her contemporaries. Such listening gives us a clearer sense of the composer’s individual soundworld and an understanding of how aspects such as orchestral writing or string quartet textures are presented in piano music, for example. I've always had problems with "you have to", when it comes to interpreting music. As in, "You HAVE TO know the Beethoven quartets to understand his piano music" or "You HAVE TO know Schumann's love letters to Clara to play the Fantasy". In a blind listening, no one can say definitively that 'yes', I clearly know and understand Beethoven's late quartets. But I like this "listening around". Especially when it's expanded to other composers of the time period. Composers always notate their music with certain assumptions that performers would understand the written symbols. Seeing and understanding works of the time could give a fuller picture of what was implied or taken for granted in musical notation. Conversely, hearing a performance which I may dislike is never a waste of time. When I heard Andras Schiff perform Schubert’s penultimate piano sonata (in A, D959), a work with which I have spent a long time in recent years, I found myself balking at certain things he did to the music – not that anything was “wrong”, it was simply not to my taste. But one thing I took away from that performance was his pedantic treatment of rests in the first movement (Schubert uses rests to create drama, rhythmic drive and moments of suspension or repose) and this definitely informed my practising when I next went to the piano to work on the sonata. I confessed in my last post that I don't really care for Martha Argerich. Obviously, many people, including many musicians I love and admire, do care deeply for her music making. I don't necessarily dislike her music, and there are moments in her performances that I like but...On the whole her playing doesn't excite me. But I would be remiss if I ignored her completely. If great artists value her work, I should try and pinpoint what her attraction is to others, and perhaps add some lessons into my own playing. Just because I want to discover my own artistic voice, does not mean I'm excluding any opinions from outsiders! Most of us are limited by our own imagination, experience and knowledge and great performances and interpretations can broaden our horizons, inspire us and inform our own approach to our music. But listening at concerts, and particularly to recordings and YouTube clips does have its pitfalls too. There may never again be a time when performers will make a living off of recordings...But all the same, unless you are watching videos from an artist's personal page, or from the official page of a record label, please do not listen to recordings on YouTube. We want to ensure that videos are monetized for the proper people who created the content, and that is very difficult to do on YouTube. (My own videos have received copyright claims for being performances of Menahem Pressler, and Lili Kraus, and while I'm flattered, I clearly am not either). We can be sure that whatever money is coming in through streaming is getting to the right people if we use Spotify or Apple Music. Recorded performances capture a moment in time and while they can certainly inform our playing, they can also become embedded in our memory and may influence our sense of a piece or obscure our own original thoughts about the music. This may lead us to imitate a magical moment that another performer has found in a note or a phrase – a moment over which that particular performer has taken ownership which in someone else’s hands may sound contrived or unconvincing. What a magical way to say what I've tried to convey so often. Perhaps we can take general approaches to artistry, but not exact interpretations. But how often do we try to get inspiration from how someone else has interpreted a piece. Much better to focus on people as unique individuals, rather than gods of detective work. The other problem with recordings is that some performers may take liberties with the score to make certain passages or an entire piece more personal. This tends to happen in very well known repertoire, where an artist will put their own mark on the music to make it their own, while not always remaining completely faithful to the score. They might take liberties with tempo or dynamics to create a certain “personal” effect. Thus, some recordings may not truly represent what the composer intended, yet these recordings have become the benchmark or “correct” version. I suppose I have made similar arguments before. However, I don't like the term "composer's intentions" and always recoil when I hear it, no matter the context. In the New Year, I will deal with this term extensively! So when we listen we should do so with an advisory note to self: that recordings and YouTube clips can be helpful, but we should never seek to imitate what we hear. It is the work we do ourselves on our music which is most important, going through the score to understand what makes it special, and listening around the music to gain a deeper understanding of the composer’s intentions so that our own interpretation is both personal and faithful. And here we come rather full circle. I recently discovered the Mendelssohn Octet. What an INCREDIBLE piece of music. I don't know why I never listened to it, I've known about it for at least a decade, but just this weekend I decided to give it a listen. This music spoke to a part of my musical soul, and woke that soul up in such a way that I didn't want to play this exact music in particular, but I just wanted to make music. So yes, listen to artists that inspire you, listen to works of great composers, but have the right intention. Be inspired not to copy them, but to follow them in making beautiful, inspirational and artistic music.

Sometime in the midst of my master’s degree, after I had read Kenneth Hamilton’s After the Golden Age, I came up with a study that I think might demonstrate the effects that listening to recordings has on individuality in one’s artistry. At this point in time, I was very frustrated with the general state of piano playing. So many people seemed to love Martha Argerich, and I didn’t get it (I still don’t get it but that controversy is for another post). All this I ruminated on in my last blog post.

As I entered my doctoral degree, I thought I might have the chance to work the study into my program, but as graduate work goes, I got too busy, ended up going another direction in my research and lost the chance to have plenty of student pianists nearby to test my hypothesis. I thought it might be relevant to share the general outline of the study. Maybe someone will one day take it up and test it! The procedure is simple enough: have two groups of pianists, likely undergraduates though their technical capabilities by no means need be similar. Each group would be given a score of some obscure work, likely from the early classical period, with relatively intermediate technical challenges. The score would make no reference to composer or style. I would recopy the score on notation software myself and include only the essentials: notes, rhythms, tempo indication, and meter. Dynamics, articulation, phrasing, metronome marking would all be absent. The test group would be given free rein to practice and prepare the score for performance in a given time period. The only stipulation is that they may not consult with any other person in their preparation of the score. The control group would also be given free rein to practice and prepare for performance in the same time period. They also may not consult with any person in their preparation, but, they are given a recording of the score which they must listen to every day. In the recording, which I would make with an attempt to sound stylistically appropriate, they would hear distinct choices in terms of tempo, articulation, dynamics, phrasing, rubato, etc. All participants would, after the same amount of preparation, record a final performance. These recordings would be sent to adjudicators. These professional musicians would be aware of the score, plus an edited score representing the distinct choices I made in the recording. Adjudicators would be asked to grade how closely each group adhered to distinct, observable and (relatively) measureable interpretive choices in the recording. My hypothesis is that the control group would make interpretive choices similar to the recording, more often than the test group would. As my goal in the recording is to not make controversial interpretive choices, I suspect that students in the control group would, without realizing, adopt the logical interpretive choices that I had made. While the test group may also make several interpretive decisions similar, given stylistic conventions, inevitably, something such as exact metronome marking, or articulations in a melody, or dynamics, will vary given complete freedom. Upon further thought, it may make sense to make one controversial interpretive decision in the recording and see how many of the control group go along with it. Secondly—What I would include in the score could change. I think it’s important to have as blank a score as possible, so that people’s artistry would be observable on a nearly blank slate. Perhaps I wouldn’t even need a tempo marking, “Allegro” for instance. That would be one way to see who in the control group would resist the pull of recordings enough to question what they were hearing. For instance-imagine having no tempo marking for the opening of Mozart’s Sonata K 545, and hearing it played adagio. One could feasibly, if you never heard this work before, yet intimately understood the style, not question the choice of tempo at all. Thirdly, it would be interesting to run this study with proficient high schoolers making up both groups, as well as only graduate students, even run it with only professional musicians. Then compare the rate of variance at all 4 levels. What if, on the whole, the control group’s interpretations adhered to the recording at the same rate greater than the test group, whether or not we are dealing with high school musicians, or professional musicians? I think the results of such a study would be fascinating. None of this is meant to discredit professional musicians, or students. The simple aim is to observe the roots of our artistry, and to find one way of explaining how our general sense of style in interpretation might have a fundamentally different basis than that of artists when the composers of the classical canon were themselves writers of ‘new music’. |

"Modern performers seem to regard their performances as texts rather than acts, and to prepare for them with the same goal as present-day textual editors: to clear away accretions. Not that this is not a laudable and necessary step; but what is an ultimate step for an editor should be only a first step for a performer, as the very temporal relationship between the functions of editing and performing already suggests." -Richard Taruskin, Text and Act Archives

March 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed