|

A lot of studying the piano is learning to copy, from our youngest years through at least until completing undergraduate education. Initially, this isn’t a bad thing. We need models to learn:

But there comes a time that we want to move away from copying. Until we do, we generally only function as accidental, or perhaps unintentional, pianists. We’ve done everything by chance, regurgitating what we’ve learned instead of processing and adding value to everything we’ve been taught. Sometimes when we think we’ve gone off on our own, we haven’t actually done so. I’ve argued that the act of performing is at least as important as the texts on which our performances are derived. I believe our ears are easily manipulated by what we hear and most of our performance decisions are not truly our own; see case studies in Beethoven and Liszt. And so I’d like to suggest embracing what I have decided to call 'intentional pianism'. What makes a great pianist stand out? Our favorite pianists have at once a pianistic voice that is all their own, that sounds completely familiar, and simultaneously keeps us thinking and guessing. They’ve studied all the rules but have commanded the authority to break them. They have a sort of intentionality to the way they play music. All this is not to suggest that intentional piano playing is limited to the great masters. Some of my absolute favorite musical memories are from pianists who are not famous to the general classical music population. Some of the most distinctive performances I’ve seen were by students who brought an energetic commitment rare among artists, others are from professional artists who have sought their own career path, whether to pursue unique repertoire or venues for their performances. Anyone can play with intentionality. Nor do I want to suggest that our educational system is failing students. I’ve benefited from studying with an incredible, diverse group of piano teachers, all of whom are brilliant, and largely fall into the category of a ‘traditional’ piano teacher. And there’s nothing wrong with role of traditional piano teacher, in fact, traditions are essential. But to step out as performers with a personal intentionality, we need to use traditions as a stepping stone, not an end in themselves. Our professors in lessons and classes only have so much time to help us reach the level of being a unique artist. My goal with this blog and other future endeavors is to supplement the great teaching that goes on in piano lessons and schools of music. I believe some of the keys to being intentional include:

With this blog, most of all, I hope to outline how one can become a truly independent, a truly intentional pianist. Over the course of this next year, I’m going to present 5 blog series along with several standalone posts. First will be Extraordinary Recordings, a series studying several of my personal favorite performances on record, focusing on what makes the performer so unique. This will be, in a sense, a series of 9 case studies on pianistic intentions. Simultaneously, I will report on my viewing of the Cliburn Piano Competition, my favorite performances as well as thoughts on the repertoire chosen, and nature of competitions in general. What better way to ruminate on the state of intentionality than by studying this competition of world-class, young talent? Later on, with the hope of inspiring some summer reading, I will release a series of posts on Influential Books. Some of these will be explicitly musical, but several will be from outside the musical world. In the fall, I will be ruminating on the Coexistence of Contemporary and Traditional Classical Music. This will be in preparation for a project that I’m very excited about, which I will announce later in the summer. Finally to end the year, I will discuss my views on Performance Practice, especially focusing on my work studying the amazing pianist Ervin Nyiregyhazi. I hope you’re as excited about this journey as I am. Please subscribe to my e-mail list to the right, as I would love to keep you apprised as each new series is rolled out, as well as my projects as a performer.

A change of pace from the Messiaen...

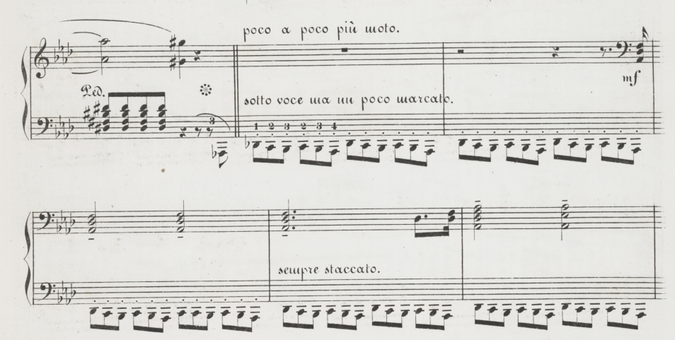

I have sat on this recording for almost a year and a half now. In general, I was not happy with this recording session and only had a couple movements of Mozart cleaned up to actually share publicly. But I’ve continued to think about this Franz Liszt run. It is messy in the beginning with a couple memory lapses but generally stays on track and presents how I’ve heard this piece in my head. But there is another reason I’ve always been hesitant to widely share my performances of this piece. I drastically depart from the standard performance practice in one notable area. Funérailles is famous for the middle section fanfare, the military parade which, as the route passes by the listener, the pianist explodes the thunderous bass ostinato with octaves. It’s virtuosic and may or may not reference Chopin’s famous A-flat Polonaise. Here’s the beginning of the section, from the first edition: Notice the tempo marking: poco a poco piú moto, or, ‘little by little more motion’ from the last tempo indication, which was adagio, in the very beginning. Other editions, including Henle’s Urtext, and editions by Emil von Sauer and Liszt student Jose Vianna da Motta agree. And YET no one plays it like this. At the beginning of this section, the second measure in the excerpt above, performers always take a new, fast, tempo. I’ve never understood this. Franz Liszt clearly marks a new tempo (Allegro energico assai) only at the climax of this section, and continues to reinforce the poco a poco piú moto until that point is reached. But performers always begin this section very fast. Are they afraid that they will not be fast enough by the time octaves are introduced and be accused of lackluster octave technique? Practice pacing yourself. You can start slowly but get to a tempo to leave no doubt in your abilities. You run the risk of the opposite problem: starting fast, and trying to get faster so that your octaves are doomed to fail. Even Horowitz succumbed to this extravagant failure and had to drastically cut the tempo back at the climax of the section. My performance of the military march here is an accurate depiction of this section, I think, and the effect of movement, the tension of the unyielding ostinato, and the pride of the moment is accentuated if this section begins adagio. It makes for a strong musical choice, but I have yet to find anyone to actually make this observation, whether in writing or in performance. Particularly listen to 7:00-9:15. The military march section begins at 7:25, the octaves at 8:30, and the Allegro energico assai at 8:50. What do you think? Give it a couple listens then tell me if you're convinced, or if you find the sudden tempo change a better choice. I'd love to hear from you! This blog title is certainly to be taken tongue-in-cheek. I don’t hate music but what I do hate—and what I think the Bernstein song that inspired the title was getting at—is the culture of what classical music has become. Stuffy concert-halls, egotistical performers, interpretations that must follow a standardized formula based on modernly-conceived “rules” of tradition. I hope to explore many of the contentions I have with the classical music world through this blog. I did not begin to truly enjoy music until just a couple years ago. There are only a couple books that have changed my life: the Bible, Stephen Covey’s “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, William Westney’s “The Perfect Wrong Note” and Kenneth Hamilton’s “After the Golden Age”. The last I read over Christmas break in the first year of my master’s degree and found it such a relief. I will surely talk about it a great deal later so suffice to say now: it addressed a side of making music that was lost in the 20th century. It inspired me to listen to the oldest recordings of pianists who studied in the 19th century. We have on record performances by people who were trained in the musical style of the time in which the great piano canon was created. These recordings sound bizarre but here are the performance practice of Liszt and of Chopin, of Brahms and Schumann, even of Mozart and Beethoven. And yet it is not the performance practice propagated by performers today, whether or not they claim to be authentic interpreters. Music was openly subjective back in “the day”. Says Richard Taruskin (another hero of mine, though he certainly goes over the top on occasion, and his repulsion towards contemporary music is alarming) regarding music as museums and performers as curators: “In musical performance, neither what is removed nor what remains can be said to possess an objective ontological existence akin to that of dust or picture. Both what is ‘stripped’ and what is ‘bared’ are acts and both are interpretations—unless you can conceive of a performance, say, that has no tempo, or one that has no volume or tone color. For any tempo presupposes choice of tempo, any volume choice of volume, and choice is interpretation.” (Texts and Acts, page 150). I have arrived at the point that anything claiming to be music is worth a listen. Popular, classical, why must we even make the distinction? I believe to tout the genius of composers of the past, or the inerrancy of a musical score is to do a severe disservice to our art and the satisfaction we can get out of performing that art. I used to be more close-minded, in music and all walks of life. I knew what I believed, that I was ‘right’ and I arrogantly defended my positions. Just a few years ago I would have openly shot down my two great music loves: Liszt and contemporary music. Now I could be satisfied playing both, or either, for the rest of my life. Music—in the most subjective and therefore true sense—should never be boring and it should always throw you for a loop once in a while. Final thoughts go to Alex Ross in a great article in the New Yorker from a few years ago: “Music is too personal a medium to support an absolute hierarchy of values. The best music is music that persuades us that there is no other music in the world. This morning, for me, it was Sibelius’s Fifth; late last night, Dylan’s ‘Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands’; tomorrow, it may be something entirely new. I can’t rank my favorite music any more than I can rank my memories. Yet some discerning souls believe that the music should be marketed as a luxury good, one that supplants an inferior popular product. They say, in effect, ‘The music you love is trash. Listen instead to our great, arty music.’ They gesture toward the heavens, but they speak the language of high-end real estate. They are making little headway with the unconverted because they have forgotten to define the music as something worth loving. If it is worth loving, it must be great; no more need be said.” |

"Modern performers seem to regard their performances as texts rather than acts, and to prepare for them with the same goal as present-day textual editors: to clear away accretions. Not that this is not a laudable and necessary step; but what is an ultimate step for an editor should be only a first step for a performer, as the very temporal relationship between the functions of editing and performing already suggests." -Richard Taruskin, Text and Act Archives

March 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed