This piece can easily devolve into banging in the repeated left hand chords and unmelodic thumping in the right hand repeated notes. There is not a lot of melody, especially considering the amount of repeated E’s in the first phrase. The pianist’s challenge is to make this piece angsty and musical.

Reisenberg does this by leading to beat 3 in measures 1 and 3. This slight crescendo to and decrescendo from the beat creates a nice phrase, so the DNA of Mozart’s theme-the repeated notes-is not played like an apology, yet it doesn’t sound pedantic. Not that the second theme is much more melodic. Is the melody in the right hand filigree or the left hand chords? For Reisenberg, the answer is the latter, but her left hand is still phrased with very precise shaping and rhythmic cut-offs. This is very string-like playing. The left hand continues to dominate when it splits into two-part polyphony, but the real magic is in the right hand. Even though it’s subordinate, this is some of the most lyrical playing for seemingly “filler” notes. How many times have you heard these 16th notes played completely rhythmically? Some people would say that every note is pearly, but I’m not really sure what that means. To me, her fast notes seem to float out of the piano, she’s playing with a beautiful, light, and even tone, yet it’s as if there’s no bottom of the keybed, no percussive beginning to any one tone. I have to say a few words about Reisenberg’s development section: The drama is unleashed here. Mozart has undertaken a really nifty compositional trick. We hear the first theme in C major, elliding with the ending tonality of the exposition. He fakes a modulation to F major/minor, a perfectly natural progression, but in the sixth measure of this section, confuses the eye by replacing Db with the enharmonic C#. This makes no difference to the listener, but it’s a nifty trick to those following the score, signalling that something is up harmonically. In measure seven, we begin a downward cascade of broken chords on the dominant 7th of F, but in the next measure, rewrites that enharmonically as a German Augmented 6th chord so that we land in measure nine in B major. This key ‘splits the difference’ between the key we start in, a minor, and the relative major, C Major. The harmony isn’t stable in this new key for long, but it’s a noteworthy achievement that we ended up here at all. What Mozart was never great with is pulling apart his themes. He didn’t need to, he could create drama with a new melody, or with these tricky slights-of-hand. Not coincidentally, the left hand lives in a range much lower than it has inhabited thus far in the piece, in a stormy pattern that’s new too. Meanwhile the right hand has some biting dissonances. While Nadia Reisenberg perhaps kept the demonic powers at bay in the exposition, they are unleashed here. The bass booms, and while I’d have preferred that she not shy away from the right hand dissonances, she tracks the dotted rhythm through the entire left hand, creating a gnarly web of melody. When the first theme comes back briefly in A major, she makes no qualms about pounding here, while not hammering. As we land on the dominant to prepare for the return to a minor, she shows off the jumps and trills of the left hand very clearly. All of these elements make the Development section come alive. It’s hard to find the right words to describe the magic that is the 2nd movement of this Sonata in Reisenberg’s hands. Certainly, I don’t dare track moment by moment pianistic tools that she uses. This is beautiful playing, which has the delicacy that so many people crave in Mozart playing, but still amply phrased and melodies differentiated with clear articulation. A visual inspection of the score suggests a busy sounding movement: plenty of articulation, phrasing, rhythmic variety and accompanimental vitality. All of these differentiations are present, yet the sound of the music is simple, straightforward and natural. The finale is more agitated than angsty. Generally I’m happy with the balance she strikes between the hands. I think Mozart creates the illusion of independent hands, each hand with its own rhythmic ostinato and melodic shape, that line up for brief moments at cadences, when the left hand has quarter notes. I think a little more left hand would have made this compositional device more apparent, and the moments of coordination between the happens ironically jarring. But, when the hands flip ostinatos for the B-section in e minor, Reisenberg’s voicing is so mysterious and the interaction between the hands so nervous, that this oddly mono-themed Rondo is a great success. Bonus: Attached to the playlist is another pianist who recorded this piece but no other Mozart Sonata--Dinu Lipatti.

convince everybody, and I dare say that my approach to the music will evolve over the next two years.

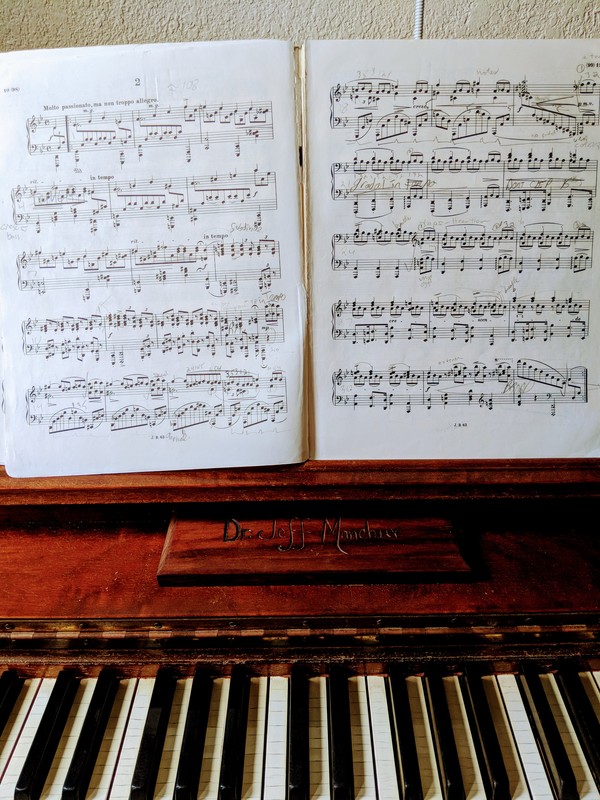

To begin with, though, I want to listen to a Mozart performer who I love. Walter Klein was not someone I knew, actually. As I started to collect lists of pianists who had recorded complete Mozart Piano Sonatas, his name came up and I started listening, and was hooked. There is so much in his approach to Mozart that I admire and want to recreate in my own way. His Mozart is full of extroverted characters, obvious phrasing, and colorful textures. To get a sense of this, I thought I would focus on the Sonata which I'm learning this month: #1, K 279 in C Major. You can hear nearly everything that I love in Klein's playing in the first few lines:

Overall, the thing I like about Walter Klein's Mozart playing is that he doesn't aim for delicate consistency. Many pianists underplay the variety that is in Mozart's scores, like they're apologizing. Klein does not. The first measure of the last system on the second page is quirky, the grace notes snappy and tempo rushing, before he returns to a melodic texture. Everything has shape and articulation, and those shapes are not even, smooth and rounded. The Development of the first movement does not have quite the variety I'd have expected. The sequential elements are often played with the same momentum, rather than each measure phrased internally, as well as having a specific role in the entire sequential shape. But perhaps this is intentional; he's letting the harmonies speak for themselves. It's like this Development section is no-man's-land, harmonic anarchy, and such phrasing would be out of place without a tonal hierarchy. After all, he makes much of the harmonic differences in the recapitulation, where even in the first theme (bottom of the 3rd page), Mozart is making creative changes. I've always found the second movement of this Sonata to be very awkward. The fortes and pianos seem rather arbitrarily placed (i.e. 3rd system, page 9), and many sections seem to disregard the time signature entirely (i.e. last two systems of page 9). But the phrasing taken by Klein makes the movement make sense. Nothing is very extreme here, the dynamics, nor the rubato. But he uses enough create phrases that have internal logic, and thus, the whole movement seems to make sense. The finale begins with a typical 4-measure phrase. The second phrase begins with the same thematic material, but ends up as a 6-measure phrase. Klein makes this phrase sound normal by playing M. 7-8 exactly the same, rather than cheapening the repeated measure with hackneyed trick like the echo effect. M. 11-18, to contrast, is a typical 8 measure phrase, except it sounds uneven: Mozart fills these measures with nearly sequential material, except he always changes something: compare M. 13 and M. 15. Or take M. 12 and M. 14, which are sequential, vs. M. 16 which begins the same, but takes a new turn. In these instances, Klein plays up the subtle melodic shifts so that this typical phrase seems asymmetrical. Because his left hand is prominent, the extra quarter note on beat 2 of M. 16 makes the shifty composing unmistakable. Ignore left hands at your own peril! Consider Klein's treatment of the repeated note motive in the second theme: measures 23, 25 and 27 each have repeated notes but each instance is treated differently in terms of dynamic and rhythmic drive. Nothing is monotonous, even though it looks monotonous on the page. This, in short, is what I love about Walter Klein's Mozart playing. It's full of vitality and variety, and perfectly encapsulates the operatic elements that I wrote about on August 6th.

(note: I've linked above to the entire album that this recording is on...the Beethoven begins on track 24, but you should take some other time to listen to more of Korsantia's recordings!)

The bass theme is played very strictly, with more separation, which I do like. Much like a Baroque style bass. I really admire how consistent he keeps this articulation in the following duets. Oh-I love the cadences in the B section: I never thought of treating these so freely, or like a cadenza! What a fascinating mix of classical and baroque styles. His a quattrois a masterclass in itself in style contrast. I love his shaping of the repeated LH chords in the theme, there’s so much music and character in this subtle voice. Variation 1-Great shading and subtle phrasing to differentiate constant 16thnotes. Variations with a single variation! Variation 2- the variety in the first variation makes the perpetual motion of this one so exciting and energetic, not at all dull. Variation 3- he really nails the style I was after in this variation, showing off the change in register Variation 4-His LH articulation sounds like it should get annoying fast for its machine-gun like precision, but he has such long shaping in mind that it’s never dull Variation 5-Again, he’s so subtle in his voicing, that you don’t realize he’s bringing out the polyphony until it’s happened, and you realized that although he began with a very narrow focus on the upper melody, he’s opened up the tapestry of texture. Variation 6- I am so glad to hear a great artist be so flexible with the tempo…It’s not free, he’s just allowing himself to make music. Variation 7- And again, he follows it up with a variation played very straight. I haven’t commented on all the cadenzas, but it’s worth mentioning here how impressed I am that he finds ways of extending nearly every single cadence in the style of the variation he’s in. Not to mention how he seamlessly works back into Beethoven’s text. Variation 8- I spoke how I was aiming for a 3rdmovement of Waldstein color here, and he has that…There’s some smearing of the pedal but it’s very tasteful. Variation 9- Props to focusing so much on the left hand where the melody obviously is…instead of the very difficult right hand. It may be easier that way! Variation 10- this kind of near rhythmic dislocation is exactly what I’m after! Also, one of the most fun cadenzas, it sounded like we were headed to some modernism. Variation 11- So here he’s rewriting the rhythm; the last eighth note of the first measure (and subsequent ones), is supposed to be two thirty-second notes, and a sixteenth rest, but he shifts the first 32ndnote to the end of the third eighth note of the measure…I love it though. It’s completely in line with the puckish character. Variation 12- again, like variation 9, a master technician at work, this time particularly for how little pedal he uses. I do like a wash of pedal for the whole harmony. Variation 13 I’m relieved that his tempo isn’t any faster here, but again, he makes so much music: the moving line, especially in the left hand is so well shaped. And props that he still chose to do a cadenza in such a difficult variation. Variation 14- I love the voicing here. Variation 15- in this and the previous variation, he a little more held back, just letting Beethoven’s notes do the work. That’s not a bad thing, nor is it bad that we get a greater dose of “Korsantia” in the preceding variations. I think it’s a true mark of artistry to show both sides in a performance: the performer’s own personality as well as the composer’s. Fugue-relieved again that his tempo isn’t too fast. I’m probably a little slower, but in the ball park. I like how he lets little motives sneak into the fore, the spotlight is never in one place. Post-Variations- I love the terraced build here, so when the 32ndnotes come the last couple pages, it really builds to a climax. That’s one apparent flaw of Beethoven’s in the piece…You get this crazy difficult fugue which ends in these climactic chords…but it’s not the end of the piece. These post variations can almost seem like a let down, but Korsantia does a remarkable job making this a true ending. All in all, I’m astounded by this performance. So much individuality from the performer; it sounds so much like Beethoven, but I cannot imagine anyone else reproducing this performance. No amount of textual study to determine the composer’s intentions will create such a thrilling variety of musical moments. None of the variations feel like the one before, and the rather dull bass theme nor the repetitive form gets old, no matter how many times the same structure gets repeated. I’m inspired by this kind of playing, not to reproduce it, but to find the depths of a piece so that I can put so much of myself into this piece as Korsantia did.

This past year I learned and twice performed Beethoven's Variations and Fugue in Eb, Op. 35, commonly known as his Eroica Variations, as the theme of the variations is the same theme as the finale of his 3rd Symphony, also titled Eroica. This was never a dream piece of mine per se. A friend of mine had played it in our undergrads, and I heard Jeremy Denk do it live once. But it's not a piece I knew much about, nor one that I could "hear" in my ear (besides the theme). I knew it existed, but beyond that, my mind was a blank slate.

So last summer, I decided to learn it, and keep my mind free of the interference of other interpretations. (I discussed the problem of being influenced by recordings in my Artistic Messages blog series last fall, particularly #4.) I thought this would be an ideal piece to see exactly how much my artistic voice would differ from that of others: this is a significant, virtuosic piece by an iconic performer, but one relatively unknown to most people. While learning the variations, I listened to just a couple people start the fugue to get a sense of their tempo, that's it. I didn't listen very long, and I tried to ignore all other details of their playing, beyond what I needed to satisfy my discomfort with my own tempo choices. Otherwise, to this day I haven't had any influence from other recordings of this piece. (Though full disclosure, I have played this piece once for my former teacher Thomas Rosenkranz, and twice for my coach Louis Nagel. Both mentors gave invaluable help and advice, yet neither works with me in such a way as to fundamentally change my interpretations. I see their influence as clarifying my vision of the piece or helping me reach that vision more efficiently). Here's the very first performance of that piece, from my Choosing Joy recital in February.

Bass plus one voice: 1:20 area-I debated a lot whether to bring out the bass, or the 'new' section-the duet. Here I'm not consistent enough with either, though I do like bring out the difference: the duet.

Bass plus two voices: 2:10- I like the dialogue here! Bass plus three voices: 2:45- I had a memory issue of a different variety in my 2nd performance of this piece too. Theme: 3:25-I'm pretty happy with the phrasing here, though some of the passagework needs cleaning up. You need this jolly feeling here, but the arrangement and texture is really heard! Variation 1: 4:05- It's so easy to over rely on the pedal here, but I'm glad that I'm not! Variation 2: 4:45- of course Beethoven would make one of the hardest variations the second one. I'm quite happy with the tempo and cleanliness of the A section especially. I don't love arpeggios, but am glad it's in the key of Eb, and not C or F#. The mix of black and white notes helps a lot. Variation 3: 6:09- there's a really tiny memory slip I'm proud to have played through. Variation 4: 6:30 area- I've debated about playing different tempos in these variations, even with such consistency in sixteenth notes in these first four. But it seems to me they're so completely different in character, that I just need to "help" their differences a little bit. Variation 5: 7:05- Tempo especially different here, I want to milk these juicy intervals in conversation. Variation 6: 8:00- Just the week of the performance I was having major memory problems in this variation, so I'm glad I rectified it here. I'll take some unclean broken octaves instead. And again, success in not over-relying on the pedal. Variation 8: 9:20- A precursor to Waldstein Sonata's finale. Everyone kept telling me to use more pedal here. I like the sound, but maybe will experiment with going further in this direction. Variation 9: 10:08- for me probably the 3rd hardest variation. Playing these chords, with such short articulation, but still making them beautiful. Not a very successful performance, though the B section was better than the A. Variation 10: 10:50. Actually one of my favorites. Besides the false, I like how it went. I'm trying to displace the meter as much as possible, each hand disrupting the other. Variation 11: 11:30 ish. Another favorite. Such a mundane melody, simple accompaniment. I actually had a lot of memory problems in the B section while learning it. Variation 12: 12:20- I guess tied with 9 for the 3rd hardest variation. My hands don't like to adjust to new hand positions so quickly, but then to play broken chords too, this could have gone worse. Variation 13: 13:06- it's up for debate whether this or #2 is the hardest variation. I'm still not convinced about how to use the pedal here. I'd take this kind of accuracy; I only completely missed the right hand note once, and a couple other times it was a little messy. I could have slowed down a tiny bit more and no one should complain, but gosh I really want to keep the energy going like I did here. Variation 14: 13:45ish- I wish I'd changed the mood more here. This should have been slower. But I like the voicing, and how I hold onto dissonances. Variation 15: 14:42- Very hard to memorize, and to phrase. And to count. I think I found a nice balance in the A sections between the short phrase articulations from Beethoven, but still maintaining a longer line. Fugue: 20:19- There's nothing so intimidating to me than performing a fugue from memory. My Master's recital had 3, including a 5-voice fugue. Listening to it now, it's been nearly 4 months since I last performed this piece, and I've read through the fugue maybe once or twice. It feels like a foreign piece! I can't 'feel' myself playing it as I listen, as I can with most of the variations. I'm impressed with the speed I have here, but I'm worried that relearning it is going to be very difficult! I'm very happy with a lot of the voicing and articulation, and besides a couple slips, the memory is quite good. This fugue is also difficult because it's so easy to play it all fast and loud. You want the feel of eroica, but without banging. Pacing is so important, and I feel like my performance doesn't get monotonous. Post-variation 1: 22:42- I never feel like I have great trills, but I really liked the sparkliness of those at 23:27. Post-variation 2: 23:38- My left hand melodic chords get very rhythmically monotonous, every repetition of the rhythmic device gets the exact same stress. When my right hand moves to 32nd notes at 23:53, I like the phrasing of the left much more. Overall, I like this performance a lot more now, than when I did a couple of weeks after it happened. I think I capture the distinctiveness of the variations so that this doesn't feel like a long piece. There's enough sloppiness that I'm eager to fix and it's nothing that a 3rd and 4th performance of the work won't fix!

And so as I adjusted my performance to align to a quarter-note pulse, the piece changed from the brooding, introspective piece to a very angry, agitated one. The piece drives forward, barely relenting, until you reach the climactic diminished 7th chord right around 0:58. Then the picardy third that follows isn't so much a ray of sunshine as it is a sarcastic "well, whatever", still angry.

I think it fits the piece really well. My teacher wanted certain harmonic tensions and resolutions in place but he was willing to go along with it. I played it this way in a couple competitions, as well as for other teachers in studio classes, lessons, and a few commented on it, a few didn't. Anyone who was very familiar with the piece clearly noticed the difference. If I encountered any resistance, I maintained that it wasn't really 'faster', my performance, it was just in the proper meter. Tap along to the quarter note, and it isn't a speedy beat! This 5-voice fugue was quite difficult to learn, but I'm rather happy with how it sounds. It sounds very busy, but there's quite a lot of clarity in this performance. This performance would come from October of 2010.

that some of the more virtuosic elements of the piece (simple as they seem to me now) were a struggle. I could tense up in the big chordal or octave sections and I imagine my rhythm suffered terribly, as did sound and voicing. I think it's also the reason I hit some clunkers; say in M. 5-6, I'm holding a fixed hand position as I shift positions and never establish the new positioning.

But this piece is a particularly dangerous one if you can't sing at the piano. It's almost made to be played "beaty", that is, EVry SINGle BEAT sounds the SAME. The first two phrases share the melody between the hands, and the homorhythmic nature, AND the range of the melody lends itself to be played so badly, so easily. I know that we worked so hard on creating a singing line, and instilling an organic rubato. At this point, even though I'd been playing it for several years off and on, you can hear the artificiality of some of my musicality. Consider the beginning. First of all, the tempo is too slow (perhaps to aide some technical struggles later. You can hear that I speed up for beats two and three, and I bet that was something we were trying intentionally, to move the phrase forward. Secondly, I make a HUGE agogic accent on the F in measure two. I'm sure my teacher was trying to get me to highlight the highpoint of the phrase, but it sounds so fake here. I do like the section that follows pretty well. I think I have a nice staccato to accent timing in measure 9 and 11. I wish measures 10 and 12 would drive just a bit more, but overall I think the musicality is natural. I remember in the "nocturne" that follows, M. 14-20, we worked a lot on rubato...I think I spend a little too much time "enjoying" the pic-up measures and they become monotonous. But, I like the sound here. Something I'm quite pleased with is the laying of voices in M. 65-82. Here in the development, takes the technique of the opening, but changes the monotonous rhythm so that the principle melody is dotted half-note and quarter-note, leaving the hand crossing in place as a filler voice. I think I highlight this rather well, and am glad I don't try to "correct" Brahms by playing the melody as if it were written the same as in the exposition. My favorite part of this piece has always been the closing theme in the exposition, and especially in the recapitulation. There's something about that surging left hand that sounds so triumphant, even in the minor key. I know my teacher warned me not to playing everything too loudly. I'm sure I was just banging, but following the advice, you hear me pull back in measure 112, again, so artificially. If I encountered a student banging in something like this, I'd encourage them to think more lyrically within forte/fortissimo, leaving the relative dynamic level untouched. So it's interesting, the first old personal recording I had, I probably remembered as worse than it actually was. I would have thought that this oft-played piece from my late teens or early twenties would have come off better. But I'd take my playing in that Haydn any day over this Brahms. (I should rerecord this Brahms!) Any music teacher worth their salt, who requires their student to make musical goals, knows to push their students towards realistic goal setting. That's not to say that a student shouldn't have a goal of "playing at Carnegie Hall", or "win the Cliburn Competition". But in order to achieve these goals, we need to formulate a series of interim goals.

The deeper you go in creating these short-term landmarks, the further you're actually getting from making goals, and the closer you are to making systems. I'm a big fan of scheduling my time, and acting in a consistent manner day to day. I wrote about aspects of my schedule when I spoke about my morning routine, and matching activities up with energy schedules. James Clear expands on this idea in an article about the benefits that systems have over goals. He suggests that if a coach of a sports team focusses on the systems built and refined in daily practices, inevitably is going to have greater success over the course of a season, than a coach focussed on winning a championship at the end of the season. If a championship is unattainable without the day to day systems in place anyway, why not put all energy and expertise into perfecting the system. Clear uses his own writing as an example. He set to a system of writing new articles every Monday and Thursday. Over the course of the year, he had produced a volume of work equivalent to 2 books. But if he had started that year with the plan to write 2 books, so many questions and unknowns would have gotten in the way: what should the book be about?, how should it be structured?, what sources should I draw on?...This is only off the top of my head. I spoke about something similar to this in a post called Dangerous Goals. James Clear's article adds elements to the discoveries I made there. Particularly, his second reason to focus on systems rather than goals. One critique that may be made about focussing on short-term systems rather than long-term goals, is that if we have no 'eye on the prize', we won't work towards anything in particular. But his point is that once we attain a quantifiable goal, we can easily lapse into passivity, perhaps regressing on the skills that took us to our goal. If we can't identify and replicate the systems that led to an achievement, even a new goal is like starting from scratch. Setting goals and working towards them is like trying to tell the future. We can't turn ourselves into something we're not. What we can do is start with an acknowledgement of our strengths and weaknesses, and work on systems, habits and schedules, that utilize our strengths. New skills will emerge, new habits formed, and inevitably we are capable of producing much greater work than ever before. So before you worry about visualizing a performance goal far off in the future (even six months is too far away), focus on your practicing. How is your practice system working out for you? How are your day to day routines supporting that system? Are you spending enough time practicing? Are you spending your practice time efficiently? Are you strengthening these artistic systems with personal growth, social time and paying attention to your physical health? Most of us would agree that the best piano playing has a certain spark of intuitiveness, spontaneity that could not be planned. Don't worry too much about planning your playing in the future. Plan your day, plan your work habits, and you might be surprised by the artistry that comes out. One writer I really admire is a guy named James Clear. He's the source of the read 20/pages a day system that I mentioned in an earlier post. He writes extensively on habit formation and strategies to formulate creative excellence. I happened upon a podcast interview with him where he expounded on a lot of ideas in this article: The Difference between Professionals and Amateurs. In short, the difference that he discovered is simply a willingness to commit to regularly engaging in one's chosen work: Being a pro is about having the discipline to commit to what is important to you instead of merely saying something is important to you. It's about starting when you feel like stopping, not because you want to work more, but because your goal is important enough to you that you don't simply work on it when it's convenient. Becoming a pro is about making your priorities a reality. I know that I myself have always had trouble committing to seeing repertoire or a recital program through to complete, professional-level mastery. When I was getting tired of practicing the same pieces, my undergraduate teacher would extol the virtues of theater actors: "They have to perform the same play with the same lines and the same actions day after day. They can't afford to get tired of it, and neither can you." It's true, the point is well taken. These professional artists had to commit to the artistic merits of their production. They had to invest their own talent to bringing a play or a musical to life day in and day out. I had the opportunity to ask a singer on tour with a Broadway musical how they achieved this professionalism. He said that in such a large ensemble, everyone's individual approach in a given night allowed for subtle variety which could only be noticed by the actors. A scene where the cast casually socializes, free of choreography, would allow for different interactions every single time. The actors could test each other's commitment to character by pushing different boundaries in an attempt to make others laugh. Even the most systematic and planned blocking allowed for variations night in and night out. I really took this insight to heart. It is the sign of a true professional to withstand seeming monotony and find artistic variations within the repetitive routine. Pianistically, we have set choreography of notes, rhythms, articulations and dynamics. We even have more subtle elements imposed upon us by performance practice, and the expectations of our teachers or colleagues. But beyond this there is still a wide margin for variation. The balance between our hands can shift between phrases to show different nuances of a story. Rubato can ramp or ease up to highlight dramatics arcs. We can explore the extremes of individual articulations; staccato does not just mean detached. A professional pianist shows up with regularity to explore these variations while the amateur pianist explores a piece only when, and until their inspiration lets up. Even the pianist who moves on to pursue something else, even if practicing consistently, but not consistently pushing one's understanding of certain repertoire, will never reach the same kind of professional artistry that others who show up and dig deeper will.

I thought that a good summer project would be to revisit some old performances of mine. The oldest recordings of myself that I know to be in existence are from my second year of my undergraduate studies. I haven't found the CD of that session, but I'm sure it's somewhere in my home. I do have my junior and senior recitals, plus several other recordings from my undergraduate years, not to mention all recitals I've done since, and non-recital sessions of other works too. I'm lucky that I've made sure to get decent recordings of almost all major repertoire i've learned.

My memory would tell me that my piano playing back in the day was awful. I've improved technically since then, and clearly I had no idea how to listen to my own playing, interpret music correctly, or practice for strong, individual performances. As I listen back, I was actually quite wrong. I don't hate my playing from my late teens and early twenties. I hear problems in it, but I also hear an individualistic artistry which I recognize as an early version of my playing today. So I thought I'd share some old personal recordings and comment on them. First up is my Junior recital from January 19, 2007. This was my first full recital program ever, including Bach's Prelude and Fugue in D, WTC II, de Falla's The Miller's Dance, a couple Debussy Preludes, Morel's 2nd Study in Sonority, (maybe something else?) along with this Haydn Sonata. This date is the only time I ever wore a tux with tails, rented for the occasion, and for some reason, I thought so much hair was a good idea.

that one of my biggest issues was a tight hand and wrist, likely due to under utilized finger position, and poorly integrating all of my upper limbs. You can also hear it in the scalar passages like M. 36-37.

Some of the musicality is naive. You can count out all of the fermatas, they're far too unoriginal and ill-contrived. I would like to hear more detail in the articulations, especially a closer attention to slurs. A lot of "hits" are the exact same strength, i.e. M. 74, 76. But on the good side, I do back off for M. 78 to create a nice little line. There are other moments where I listen and match the tension and release of a line well, say M. 60-61 I really like how I listen to the ends of phrases; M. 4-5 and M. 6-7 make a nice pair, and M. 10 captures the confusion of landing on this strange chord really well. Overall, it sounds like I do get the jocular character of this piece quite well. I don't have all the tools to execute it yet, but I do hear something in my playing that I like, and I'm grateful that I had great teachers who heard it as well.

The first day of my first piano repertoire class in the fall of 2017, I gave my students a quiz. There were no wrong answers per se, but I was interested in presenting them some pianistic problems, or, challenge some commonly held assertions about the piano repertoire.

One of the questions that I asked was:

On the surface, this is a simple matter of confirming whether or not the piece was in triple or quadruple meter. Perhaps some considered whether it was actually notated in 4/4 with triplets, or in compound 12/8 time. But several students, including some who had performed the piece quite recently, gave pause, simply for the fact that I asked a seemingly obvious question. They were perhaps more perplexed when I asked a follow-up question:

In some ways these were trick questions. Tricky because a) the question of time signature seems relatively uncontroversial, and in fact, obvious; b) because we all have a pretty clear sense of tempo in this movement. It has to be some sort Adagio, no? Well most people fail to realize that the time signature in the Moonlight Sonata's first movement is actually cut time. Though the tempo marking is Adagio Sostenuto, I always like to ask what is 'slow and sustained'? Students don't often think about the connection between the tempo marking and the meter marking. To me, the tempo marking relates directly to the note value of the basic beat, as revealed in the time signature. Therefore, the half note ought to feel like the basic beat, and it's the half note which ought to feel slow and sustained. Could it be that most people play the famous first movement of Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata too slow? Well most performances nowadays are so slow that one cannot sense the half note as a beat. It's possible to hear this movement with the half note as a slow beat. It sounds faster to our ears, yet I think makes considerable sense so that the harmonic rhythm doesn't seem intolerably slow. Besides, when you count the quarter note in most 'slow' performances, the beat is actually rather fast, not anywhere near a sense of slow and sustained.

|

"Modern performers seem to regard their performances as texts rather than acts, and to prepare for them with the same goal as present-day textual editors: to clear away accretions. Not that this is not a laudable and necessary step; but what is an ultimate step for an editor should be only a first step for a performer, as the very temporal relationship between the functions of editing and performing already suggests." -Richard Taruskin, Text and Act Archives

March 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed