|

DAY 5

I’m wondering about the strategy behind the programming.: many of the quarterfinalists that we hear today are playing unabashedly all-romantic programs: Schumann and LIszt, Liszt and Rachmaninov, Scriabin and Chopin. The ones that don’t match this trend are largely playing virtuosic staples. It seems there was generally a lot of variety in the Preliminary round repertoire to give a rounded overview of one’s playing and now they dig into what one does best. ---------- Both Su Yeon Kim and Leonardo Pierdomenico paired nearly 15-minute long Liszt works with a nearly 30 minute romantic work of virtuosity. Both of their Liszt (Kim’s Vallee d’Obermann and Pierdomenico’s Ballade No. 2) can very easily succumb to ugly, unmusical playing. Both have incredibly lyrical sections but each hand is always split between melody and rhythmic/harmonic filigree of one kind or another. If you’re not listening so intently on the balance between the parts, and the resonance of the melody, you’re going to get bad Liszt playing that the Liszt haters always chide us LIszt lovers for. I thought both managed this task extremely well. ---------- Shmukler had a very orchestral Bach/Busoni Chaconne, and a very pianistic Petrushka. While I probably liked other performances of the latter better so far, his control was incredible. He was able to sustain extremely loud texture that was still well thought out and balanced. Then, he could contrast that with the softest, most delicate sounds. A rollercoaster for our ears! ---------- I must admit that I’ve never really listened to Scriabin’s 4th Sonata and after Dasol Kim’s performance, I’m eager to pull out the score and give it a closer study. In his playing, you clearer hear the delineation between the old Chopin elements and the new, truly Scriabin-esque elements. His Chopin Preludes were flawless technical events, and a lot of his musical decisions stood out too. In the C major prelude he drew out all the juicy appoggiaturas. He made a lot out of the easily cliched e minor, with an unrelenting through-line phrasing to the climax. In the Db major, he utilized some great left hand voicing in the B-section to make us forget that Chopin was just repeating himself over and over again. ---------- Tristan Teo played Bach with quite a lot of harpsichord-esque detachment that I said earlier I was no fan of...But he really convinced me otherwise, given his polyphonic balance in the fugal sections. Not only was each voice simultaneously heard at any given time (vertically), each voice had a beautiful, sensitive shaping (horizontally). Very excited that he played the Kapustin Variations, such an entertaining piece, full of notes but well worth it. Teo let loose here after a more conservative Bach and Ravel. ---------- The argument about facial expressions and hand gestures is inevitable in every competition. In 2013 it was Alessandro Deljavan. Today it will be over Martin James Bartlett. I always come down on musical decisions based on sound alone: does it matter if it's in the score, does it matter how you redistribute a passage if you can’t tell how it was written just from listening. But this is different because visuals can alter our interpretation of sound. Bartlett plays with plenty of hand and arm motions inherent in his physical approach to make the sounds, but plenty are added for dramatic flair. His facial expressions are quite over the top. I understand that they help performers, I do some, but isn’t there a reasonable limit? I hope I limit my facial expressions to what I do in normal day life and conversation; I can’t imagine that Bartlett ever naturally makes the facial expression he made as (or even before) he started Widmung. He’s someone I need to go back and listen to audio only (as I listened to his first recital) to see what I truly think; it was hard for me to take this one seriously. ---------- It occurred to me that Daniel Hsu’s Chaconne sounded more like an organ. In the organ, you can change the color and sonority, but only at an appropriate time where you can shift the stops, not just by touch on the keys. Hsu had plenty of beautiful consistent and varied sound, and a variety of articulation, but it's his sense of time that precedes everything else. The most coveted thing an organist can change at any given moment is the manipulation of time for expressive purposes. I thought Hsu understands Bach (or Bach-like music, taking this Busoni arrangement, plus the Beethoven from the Prelims together) in this way. ---------- Yutong Sun’s program wins as my favorite so far, even in only that he programmed the Eb/D# minor Prelude and Fugue. The Well-Tempered Clavier is my favorite Bach by far and I believe he’s the first one to play a selection in the competition. This is one of my favorites of the 48. And he played it right up my alley in terms of style: slow, restrained, very legato and a slightly romantic approach to rubato. His Bartok Sonata, a piece that easily falls into the trap of constant pesante playing, was an interesting take. It wandered a lot more than I’m used to hearing, and it made me wonder if there are more folk influences than I’d previously attributed to the piece. ---------- More interesting programming to close the night, from Luigi Carroccia. He got his traditional fare in with some solid Chopin, then played two obscure works, both from composers not known for their concert music. Czerny, obviously is best known for his mindless exercises and slightly more musical etudes, if not known solely for being a student of Beethoven. But he also wrote plenty of concert works. I thought this was a really gutsy move as most people are going to listen to such a work with the predisposition that they are hearing music empty of substance, but only fluffed up on virtuosity. Meanwhile, Kabalevsky is known for his children’s piano music, and yet at least one Sonata was championed by Horowitz. I was especially excited by the Kabalevsky, it was not at all the kind of work I expected to hear. DAY 6 Tchaidze opened the day with some Schubert. The Ab Impromptu can sound so monotonous, given that so many measures have the same rhythm: pick-up 8th note, followed by a quarter note and a dotted quarter note. If you play the same rhythmic nuance again and again the piece sounds so choppy. Tchaidze did not fall into this trap, every phrase sang through beautifully. His choice of Prokofiev’s 8th Sonata to close the program was satisfying. It doesn’t have the immediate appeal of the two before it, but has plenty of beautiful lyricism as well as requiring substantial chops. ---------- I followed along in the score with Kenneth Broberg’s Scriabin 4th Sonata just to get a sense of the writing. Scriabin falls in line with several composers where the look of the music in the score does not belie how it actually sounds (consider Schumann where seemingly monotonous rhythmic patterns hide beautiful phrases and harmonic patterns). In Scriabin’s case, this music looks stuttered; so many rests and broken phrases that in performance, with pedal, have to sound like full sentences. I have extra respect for Broberg and Dasol Kim yesterday for pulling this off. Broberg’s Dante Sonata succeeded in the same way that So Yeon Kim and Pierdomenico did yesterday. Beautiful attention to shaping, rather than the virtuosity by itself. Furthermore, he added so much drama to this piece, the narrative elements were on display: the demonic sections extra aggressive, the spiritual sections extra romanticized. ---------- I don’t recall Tony Yike Yang making as many faces in the first round as I noticed in the first movement of his Scriabin; but they seemed less frequent in the finale, and in his Liszt, so perhaps the more difficult, the more still his face is! I find his hand gestures largely uncontrived. I particularly loved his Liszt, more than most performances this round. It isn’t easy to capture the ebbs and flows of this piece, and he was able to engage the listener from beginning to end. I especially loved how much the second theme drove forward, while still capturing its majestic nature. ---------- I was born to love Hans Chen’s second program: a thorny Shostakovich Prelude and Fugue, 3 short works by a living composer, and the Liszt Sonata. The Ades I was most excited about. I don’t know these particular works but other pieces by the composer (check out Darkness Visible) have been mind blowing. He’s got a very special style, and writes very difficult music (being a great pianist himself), that is usually written in an obscure metric system. Hans Chen of course had these Mazurkas memorized and played them with so much sparkle. It’s hard to hear the Mazurka dance on first listen, but they danced in some way! It would take me another listen or two to describe exactly why I liked Chen’s Liszt so much, even more than Yang’s. There was something unsafe about it, perhaps ---------- Yekwon Sunwoo played Schubert’s c-minor Sonata like Beethoven, or maybe that’s partly because I’ve been listening to some of today’s competitors out of order and previous to this, had heard Rachel Kudo playing Beethoven Op. 31/3. The finales of each are not dissimilar in that each is a driving 6/8 meter with plenty of dance and drama, and they are in related keys of Eb/c. I think this Schubert is very appropriate to play like Beethoven, and I imagine the choice of c-minor was not unintentional for Franz, who was dying, having just experienced Beethoven die in the past year. The incessant rhythm of the finale can easily become monotonous, and by not shying away from intense climaxes, Sunwoo avoided the worst of it. ---------- If you think about Sonata form being all about the structural dissonance resulting from the modulation away from the home key, and ultimating rectifying that musical material back to the tonic (as some theorists do), Rachmaninoff’s music fits into that box with much difficulty. I find it especially obvious in this first sonata: it’s not enough to have two themes, each in a different key to begin with, the modulation is an essential part of the drama. His second sonata is more popular I think, specifically because it doesn’t try to be a grant sonata in the way the first movement does. Brevity was Rachmaninoff’s friend when writing for solo piano! The first movement tends to wander aimlessly in the exposition. The development affords lots of excitement, though, given that section's ability to adapt to any number of composer’s styles, such as Rachmaninoff’s own. Honggi Kim is in fine form in this section, putting Rachmaninoff’s orchestration of the piano into beautiful sound. I wish the rest of the piece could hold my attention, but the pianist is always fighting an uphill battle in this piece. ---------- I wonder how strict the Cliburn is on their time limits? Rachel Kudo began Carnaval, a half hour work, nearly 20 minutes into her 45 minute recital and without going off in between pieces, her recital ran to 50 minutes. There’s no way that program was going to fit into the time slot. Yesterday, Daniel Hsu’s program ran a couple minutes over (but he went off in between pieces), but Yuri Favorin’s program was over 50 minutes long too. ---------- Jurinic chose what for me would be the most daunting composer to begin a recital with-Debussy. When you’re so exposed in terms of color and control, I’d rather have had a chance to sink into the piano first. There were a couple moments I questioned the consistency of his texture, but it might have been my imagination. His Images were beautifully crafted, voiced and shaped. I think Debussy’s music responds well to a subtle rubato, and he had it perfectly timed to complement his pianistic colors. He chose another long romantic sonata, whose composer doesn’t necessarily fit sonata form well. Maybe there’s a way for me to shift my listening to understand this music better, but I haven’t figured out how to reconcile classical form with romantic composition. I love them both, just rarely together. It seems these pieces work well moment-by-moment, rather than in the long term. I was waiting for Jurinic to have a truly Schumann-esque moment of fantasy, and I never really heard it. The primary theme of the first movement could use a lot of impetuous drive, but I heard it stay rather ‘in the pocket’. Or his shaping of lyrical phrases seemed overly-planned, rather than spontaneous. ---------- I decided to give my hand at predictions today, as I won't check the results until the morning. My favorite recital of this round goes to Yutong Song. Top 12 is: Su Yeon Kim, Pierdomenico, Dasol Kim, Bartlett, Hsu, Sun, Tchaidze, Broberg, Cheung, Yang, Sunwoo, Chen. ---------- And I was 10 for 12. I included Su Yeon Kim and Bartlett, the jury did not, instead choosing Favorin and Honggi Kim. It appears Bartlett has become the audience favorite in the competition, a lot of social media commentary is most upset about his exclusion. I admired his first recital especially, and can see why many would gravitate to him.

She concertized as a young woman around Europe, but settled to raise a family, continuing performing during World War II. Moving to the U.S.A. after the war, she never gained a significant performing career, even though at her age she still played with impeccable technique and musicianship. The recordings we do have from her exist from this late part of her life. (See this website for my sources, and more, on this incredible life story.) Typically I believe in supporting artists by, at the very least, streaming their recordings from legitimate services like Spotify or Apple Music. Unfortunately, most of Freund’s recorded work is unavailable anywhere, even secondhand CDs. YouTube is the best way to make her art visible. I’d like to continue my focus on Brahms. Seeing as how he adored Freund’s playing, it is noteworthy to hear her approach to his music. What old performance practices, perhaps things decried today as outlandish techniques, do we hear from this legitimate, audible record of the composer’s intentions? To see, let’s briefly walk through just the first movement of Brahms Sonata No. 3 in f minor, Op. 5. My hope is that illuminating some of the techniques in her performance will give you a greater appreciation for her extraordinary intentions in music making. This is quite a different approach than I took in the first post about Glenn Gould! I’d recommend listening to the first movement in its entirety with the score, read my post and check out the specific spots, then take some time to listen to the Sonata in its entirety, perhaps without the score. You’re in for a treat! Significantly, throughout the performance, we hear plenty of unmarked arpeggiation of chords, or anticipation of the left hand. These unmarked forms of subtle rubato are so common amongst early recordings by pianists trained in the 19th century and are so often vilified as ‘sentimental’ today. You can’t perform asynchronously what is marked to be played synchronized! And yet, they do. Consider measure 7, (hear it here). Asynchronization of the hands is tricky to hear, so much that you probably need headphones on to hear it properly, but the left hand is slightly agitated, often anticipating the right. You’ll also hear this technique in nearly every lyrical area. Consider the second theme in the first movement (measure 39). The left and right hands are so asynchronized that one would almost hear this as Chopin. Often times these techniques are closely related to polyphonic playing. Pianists create more layers by arpeggiating or asynchronizing the hands, allowing our ears to catch up to hear melodic lines that we otherwise would not be aware of. In doing so, the harmonic structure and natural counterpoint is laid so much to the fore. Freund is incredibly sensitive to the polyphony Brahms himself wrote in. Consider the c# minor section of the development (heard hear). Each voice is matched perfectly to itself, and balanced with each other so that the canon is easily audible. At the same time, the general harmony of the phrase has drive and direction. Contrast that with the searching melody which happens at the key change to 5 flats. The syncopated right hand chords are played as triplets, rather than eighth notes but this lilt provides rhythmic anticipation which suggests the harmonic stability is an illusion, pointing us towards the true, unstable, development which will break out momentarily. Consider her tempo. The first movement begins at a quarter note around 70. The second theme is actually played faster, beginning in the 80s and accelerating (even before the un poco accel) to the 100s. I’ve heard it argued that all tempos in such classically minded composers must “live under the same roof”, that is, to be very closely related to each other, considering that they share the same foundation. I’ve also heard it argued “you don’t feel the same in the living room the same way you do in the kitchen or bathroom!” Freund, and pianists of her generation seem to feel closer to the latter: themes have their natural tempo which must be taken to promote the true character. The un poco accel at the ended of the exposition are treated as significant events, there’s nothing ‘little’ about them! Furthermore, they are more a sudden change of tempo, rather than gradual. But she slows down significantly for the cadences, especially the final resolution on the repeated Db major chords. She’s extremely mindful of the structural significance of every measure she plays. Listen to the last 23 measures (heard here). This is the first theme heard in the parallel major, and the tempo is just a little faster than the opening of the movement, mid-80 beats per minute. The Piu Animato jumps to nearly 100 beats per minute, which is fair enough. But the hemiola section 5 measures later is suddenly at 170, without provocation. Would you have noticed that if I didn’t point it out to you? I’d wager you wouldn’t, and that’s the key. Unless you’re counting along with a metronome like I was (for analysis purposes!), you aren’t consciously aware of these vast changes of tempo. Our primary focus ought to be on the transformative artistic picture which she is creating. The tension her changes of tempo create are more important than the means used to create the tension. I’d like to point out one more minor detail which sets mature artists apart from mortals like myself. In the development, 8 measures before the key signature returns to 4 flats, the left hand begins with a dotted sixteenth, 2 thirty-second note rhythm (heard here). She voices the thirty-second notes very clearly, instead of throwing them away. In fact, it’s almost like the first short note has a slight accent, which typically is a big no-no. But she has a specific reason for paying attention to these short notes: in the fifth measure of this motive, the thirty-second notes are followed by an eighth note, jumping up a tenth. Given her attention to the short notes preceding, we can hear the stretch of that interval. It sounds like one voice, where as so often, this motive sounds pointilistic, like two different instruments, which given Brahms’s phrase marking, is not the intention. On a closing note-there are several other Etelka Freund performances out there, other Brahms and a few other composers including Bach, Lizst and Bartok. Check them out. They all sound like Etelka Freund, which is a mighty fine accomplishment. If we inevitably are influenced by music around us, as I will always argue, we’re never going to present a sound authentic to only the composer. Rather than sounding like a neutered version of someone else’s impression of the composer, we might as well make an intentional effort to sound most consistently like ourselves. DAY 3

Luigi Carroccia was the first competitor to close his recital with the Hamelin. I’m glad someone had the guts to do so. That’s your last impression you leave the jury with and most people opt to leave that impression as something standard that everyone in the jury is likely to appreciate. It probably worked out well for Carroccia that he came later in the Preliminaries, as most of the jury had likely developed their own thoughts on the Hamelin by this time. Also that Gluck arrangement with which he began his recital was magical! ---------- Ambrosimov was an alternate in 2013 and this year again. I’m impressed he had the motivation to get the Hamelin memorized just in case. I was surprised to enjoy his Petrushka. It’s not that I dislike the piece, but I usually tire of how it’s played in the competition. Maybe I like Petrushka when it's played purely like an orchestral piece, with none of the agogic accents you can get away with as a soloist, but can't get away with in an ensemble (say after first three notes of the first movement). This music seems to make sense to me when it’s alll about driving rhythm and color. ---------- Tchaidze played the third performance of Beethoven Op. 110. Perhaps it’s popular this time as virtuosity for performing the fugues without memory lapses. When I learned this piece, several people told stories of famous pianists they heard whose memory on the fugues faltered in live performance. It didn’t make me feel better, and I doubt it would make these competitors; young artists have a lot more at stake for a memory lapse than an established artist. ---------- Speaking of feats of memory, there are 3 fugal pieces in Broberg's program: Franck, Bach and Barber. I’ve always had problems playing fugues from memory in performance, and I admire these people so much. One slight dip in concentration can change everything. In general there are so many different fugues in this competition, a record, I wonder? ---------- EunA Lee’s Chopin sonata, first movement, second theme sat on the back end of the beat a lot, I really liked that restraint. It’s so easy in these slow expressive moments to surge forward and I think there’s a lot of artistry in making the audience wait. Also-this is different than keeping the tempo steady, she’s still doing a very subtle rubato. ---------- Sergey Belyavskiy took a similar approach with Schubert, but I’d have preferred more drive in the first movement. The wandering aspect of the piece has to do with almost spinning out of control. Even when his rubato made the tempo faster, it’s like he contracted the beats, rather than arriving at the next beat a tad sooner than expected. I have no scientific proof, but I think it’s possible to hear these differences between these two kinds of rubato, the first is a more predictable “turn the dial” sort, the latter a more organic one. DAY 4 There’s an element of fantasy in Op. 109, and Tony Yike Yang balanced that really well, paying close attention to slurs to give a variety of rhetorical gestures to his first movement. He also found some interesting polyphony in the second movement that I don’t believe I’ve ever heard. For someone to be the youngest medallist in the Chopin history (just in 2015), he’s only playing Chopin once, in the semi-final recital, the 2nd Sonata. Amazing to have such breadth of repertoire already at the age of 18. In an interview after the Chopin finals, he indicated that he was caught off guard that he made it to the finals and didn’t have his concerto prepared completely. I’d imagine given that experience, and despite a few missed notes, he’s more than ready for Cliburn. ---------- I love new music, but Elliot Carter’s scores scare me, never mind memorizing one and performing it as one of the rare pieces from the last few decades on the Cliburn. Not to mention that this is surely one of the most engaging performances of Carter that I’ve heard. Hans Chen has a lot of great repertoire, including Thomas Ades later on (even harder to memorize)! ---------- Honggi Kim played one of Arcadi Volodos’s Liszt ‘improvements’. I bought Volodos’s Schubert CD when I was first getting into classical music and always quite enjoyed it. Later, when I knew Liszt better, I heard his own Liszt recordings and it’s always thrown me off. I can’t imagine Liszt would disapprove of of the transcriptions, but I’ve never found any of them convincing myself. I suppose it seems that Liszt had left enough room for color and virtuosity that I never saw a need to add more. Plus-so different than (at least my memories of) Volodos’s Schubert. ---------- Rachel Kudo has no Liszt or Rachmaninoff or Prokofiev on her entire Cliburn program. I imagine most competitors have at least 2 of those 3, but I’m not about to check. ---------- I’ve always liked Liszt’s 11th Hungarian Rhapsody. It always seemed to me to be the most evocative of a folksy origin, mainly given the opening instrumental. Glad to see someone giving it the performance, especially for not treating it as a show-piece. ---------- Of the 20 quarter-finalists, there are 6 contestants without the “Big 7” Concertos in the finals (Prok/Rach 2 or 3, or Tchaikovsky 1). But, given my enjoyment of the Prokofiev 7th Sonatas in the Preliminaries, I’m not even worried about hearing 4 Rach 3s or Tchaikovskys in the Finals (there are a lot of Rach 3 and Tchaikovskys among the quarter-finalists). All in all there is some fantastic programming coming up in the Quarter-Finals! Due to the immense number of performers and the long weekend in the USA, my listening was a little less consistent for the Preliminary round than it will be for the rest of the competition. I wanted to catch parts of almost everyone and I managed that, so I'm very happy. Onward to the Quarter-Finals!

DAY ONE

Julia Kocuiban, competitor #1 at Cliburn, also competed at the Montreal competition, where she unfortunately did not advance. Getting accepted to two major international competitions in one year is a major accomplishment, and a few other Cliburn competitors also competed in Montreal or at the Rubinstein. Julia is offering the same repertoire as in Montreal, but due to Cliburn’s intense demands, is including a Szymanowski etude, Prokofiev 7th sonata, Mozart K 332, plus the Mozart and quintet. She chose a good piece to start the competition with. If she felt any pressure beginning such a major event, she had the slow, innocent opening to settle into. She missed a few notes in the first fast section, but sure settled in after. Her Scherzo was incredible! Fiery, and she utilized a great dry sound in the octave section. And so much pressure to premiere the commissioned piece, this year by no less than pianist extraordinaire and jury member, Marc-Andre Hamelin. Wow what a piece it is! I was so taken by the colors and textures Julia brought to the piece, not to mention the energy and incredible feat of memorization, that I didn’t listen so much for the l’homme arme tune. But I’m sure after many listenings, it will be more clear. Why not make the ending of that Prokofiev just a little harder by going faster…and faster…and faster…Incredible first recital to start the Cliburn competition! ---------- I will let at least one bias out: I’ve never liked Ginastera’s first sonata…It’s such a popular student piece, which I get, it’s attractive, it isn’t the most difficult piece out there. But because of that, I’ve heard so many performances which are only 90% there…This piece needs 110% to not sound like a gimmick. Madoka Fukami certainly sounds like no student! The Beethoven Rondo is a gutsy choice. I applaud her on that level. In this style, rather straight-laced classical, I always like the LH to contribute to the character, rather than being background accompaniment. Remember that Beethoven intimately knew Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, not to mention most of composition training at that time was counterpoint exercises. Even simple accompanying figures were in his time a modernized kind of polyphony, not simply rhythm and harmony. ---------- Compare that Beethoven to the one that follows. Su Yeon Kim understood the role simple accompanying notes can play. You have to in the Waldstein or else the repeated notes would sound incredibly dull. I loved how she played the finale theme with such delicacy. It’s a reminder of why I’m too afraid to even try playing that piece! ---------- Anderson & Roe duo pianists extraordinaire and hosts of the Cliburn webcast, quoted Mozart’s critique of Clementi during Pierdomenico’s performance of the latter: “he’s a charlatan without a farthing’s worth of taste.” We laugh at that now, but what can we do with that musically? How did Mozart hear Clementi’s music to say that it has no taste? How did he hear his own music? That rivalry or all the others across music history should have drastic ramficiations on how we play the music of the different composers. I don’t think Pierdomenico played Clementi quite like Mozart; it had lots of Beethovinian drama. But I can see the temptation isthere to neutralize Clementi so it sounds more Mozartean. I thought this guy had the most “Hamelin-like” sound in the L’homme Arme so fa. There’s something about the restrained energy, careful control of rubato but with clarity of texture. And he’s got the torso stillness of Hamelin’s technique too. This is not to say it’s the best, or most authentic performance. It just points to a noticeable intentionality of sound. ---------- Last point of Day #1—I did not expect to be so thrilled by 2 performances of Prokofiev’s 7th Sonata. Alina Bercu and Julia Kociuban gave exceptional, thrilling performances. In each case, the piece sounded unique to them, hearing and watching them play, I couldn’t imagine any other interpretation. I’m rather excited to hear it again! DAY TWO I was thinking during Dasol Kim’s Haydn: we all acknowledge that Haydn often used musical humor. And sure, some of the humor is innate in the score, written in by the composer. But performers ought to be able to add to the humor aspect. An important part of hunor-time-can only be generally suggested by musical notation. And it occurred to me in something like the finale, with so many patterns repeated within a section and within the piece: why not change the joke. Vary the nuance and tone if the composer uses the same words over and over again. Performers can keep the humor aspect alive, rather than repeating the punchline. ---------- Tristan Teo “cheated” in his Beethoven op. 110, redistributing the cascading 32nd notes of the first movement. I'm of the opinion that if you can't tell by listening, play it with your toes for all I care. I played the same passage the same way. But I have to wonder if there would be a jury member who would care. ---------- I think Caterina Grewe approached repetition and humor much the way I was talking about above. --------- Philip Scheucher, I believe, is the only performers to program a woman composer in the competition. Ive listened to Lera Auerbach’s preludes extensively so i was glad to hear it. I was amused the audience didn't know when the piece was finished, didn't clap and so he carried on with Liszt. It made a nice contrast, but I would hope that if more performers took the chance to play this music, slowly audiences will get used to the cadence of contemporary music. You can hear harmonic closure, but this group apparently wasn't ready for it! ---------- I was very pleased with Martin James Bartlett’s legato in Bach. I'd go even more legato myself, but I always prefer his articulation to unduly choppy. The harpsichord, even though it has no sustain, also has no dampening. I've always felt it had enough resonance to merit a normal legato on the modern piano, not to mention plenty of pedal! ---------- Interesting that a couple people programmed the Franck/Bauer work during the competition. I wonder if these competitors are aware of Harold Bauer’s mannerisms in performance, and what effect that would have on their interpretation. Transcriptions always pose an interesting challenge-do we take more inspiration from the original composer, or the transcriber. --------- Daniel Hsu hit so many strong points in my book. All from his Beethoven sonata. His introductory video mentioned his desire to remain vulnerable and I thought it came through in his playing. No hesitation to stretch time, take a breath, let the music breath. Very sensual, very appropriate in this piece (consider the tempo marking of the first movement.) This is the kind of playing I'd pay again and again to hear. Interestingly, he did not cheat on the 32nd notes. It doesn't seem worth it to me, but he made it work! TOP HIGHLIGHTS

On to day 3!

Chopin is a composer ultimately focused on sound and poetry. Gould is a performer ultimately focused on structure.

In this latter approach, the composer doesn’t matter so much as the construction of the piece. How the notes were put together mattered more than the sounds they made, perhaps in the same way that a building would be judged whether it was functional, not how it looked. Says Kevin Bazzana in his book Glenn Gould: The Performer in the Work, ““Gould was concerned with musical expression but was motivated by musical structure.” (page 13, first emphasis mine, second in the original) The function could be innovative, but only because the structure first and foremost, was. Bazzana quotes fellow Bach specialist Rosalyn Tureck as saying: “In Bach’s music, the form and structure is of so abstract a nature on every level that it is not dependent on its costume of sonorities. Insistence on the employment of (period instruments) reduces the work of so universal a genius to a period piece…In Bach everything that the music is comes first, the sonorities are an accessory.” (page 21). This universality is essential, I think, to understanding Glenn Gould’s performance. It is a universality which truly opens the performer up to playing with extreme sensitivity to musicality and expression that’s inherent in the work. That sensitivity may not be inherent in the standard practice of a piece, thus we get to hear Gould’s unique style of playing (see his recording of Beethoven’s final 3 Piano Sonatas for an example of something strange that, I believe, ‘works’). So Gould, “could ‘let loose’ in performance only with music whose structure met his standards of idealism and logic, music that he could first justify rationally.” (page 35) Chopin, not focused on structure will never sound truly revelatory and natural in someone like Gould’s hands. And that brings us to Brahms. Glenn Gould recorded 10 Brahms Intermezzi early in his career, in 1960. (Later in his career, indeed one of his last recordings, he also recorded the Op. 10 Ballades and the Op. 79 Rhapsodies). These Intermezzi, I do believe, constitute the most perfect musical recordings in existence, and they are often overlooked in Gould’s output. At first, Brahms seems not the quintessential Gould composer, especially given his controversial performance with Leonard Bernstein of the first concerto. But when we remember Brahms’s classicist bent, his love of Bach and Renaissance polyphony, his dedication to absolute music, it makes sense. These short forms (as opposed to the earlier Brahms Sonatas and Variations which Gould decried as “pianist’s music”) fit his temperament perfectly. On these pieces Gould himself says, “I have captured, I think, an atmosphere of improvisation which I don’t believe has ever been represented in Brahms recordings before…total introversion, with brief outbursts of searing pain culminating in long stretches of muted grief…” Or, in his words, these are the ‘sexiest’ recordings ever made (these quotes from the liner notes of this other volume of the recordings). Call it sexy or not, the Intermezzi are performed with incredible attention to expression of the melodic line, harmonic shaping, rubato and structural drama. Given the way he shapes and connects melodies or layers the polyphony, I truly believe that Gould could hear with better detail than a typical musician. Like Gould’s Bach, every line in these pieces sounds independent and musical. I point your attention to the counter melody on the repeat in the B-section of Op. 118 no. 2 and when the melody returns in the minor a few phrases later. I hesitate to analyze much further because of the perfection I hear, these recordings just speak for themselves. He has a way of balancing different lines to make us listen to something different every few measures, without losing what we were listening to before. He magically forces us to listen polyphonically. Clearly Gould was not a dry, mechanical performer, but was capable of intense romanticism in his playing. We hear it clearly in these Brahms recordings, evidently just because by looking at the structure first, he could see the beauty inside the functional, rational architecture that he simply doesn’t see when the elements are reversed in something like Chopin.

Rarely does a major piano competition go by than we see social criticisms of the results. Check out recent discussions about the 2017 Rubinstein, the 2015 Leeds, and the 2015 Tchaikovsky. In the first and last case, we even had jury member Peter Donohoe wade (with some disdain) into the commentary (see, in particular, his exchanges in the Rubinstein link). Someone is always going to be upset about the winner’s style of playing, will wax poetically about the insufficient jury’s decision to choose a ‘consensus’ candidate instead of another finalist, the individualist, who some loved and others hated.

I’ll admit to having these criticisms myself. I thoroughly loved that the 2015 Tchaikovsky competition discovered Lucas Debargue, and while I was upset he didn’t win, he has clearly won himself an audience and likely a successful career. I wasn’t excited by either of the 2009 Cliburn winners, but I predicted in the first round of the 2013 contest that Vadym Kholodenko would be the winner. I never thought much of Allesandro Deljavan, the competitor many loved and thought it a travesty when he was eliminated. Before the medal announcement, I also rightly predicted the 2nd and 3rd place winners. With the 3 medalists, I thought the jury found the perfect balance between virtuosity, musicianship and unique choice of repertoire that wouldn’t turn off the die-hard or casual classical fan, and an individuality, an intentionality to each performer’s pianism. This spring appears to be the season of major competitions with the Rubinstein and Montreal just completed, running virtually at the same time, then the Cliburn a few weeks later. Due to professional commitments I didn’t listen to much of either of the former two. But I’ve listened to the winners and at least one medalist at each. To be candid-I wasn't excited by the winner in the Rubinstein. If we check out his repertoire through the solo rounds, we see Scarlatti, Beethoven, Mozart, Chopin and Rachmaninoff (the standard fare, though at least with underplayed sonatas from the first three, and a diverse batch of Etudes from the latter), and some interesting Szymanowski to go along with the imposed contemporary piece. But I loved the winner of the Montreal competition, Zoltan Fejervari. As one of my friends said, “ …everything he played is standard repertoire but the combined program is so unique and really sets him apart.” His solo repertoire included Bach, Beethoven, Ligeti, Scriabin, Bartok, Janaceck and Schumann. Most of his choices were of lesser heard selections from each composer. It seemed clear to me from his programming and his manner of playing that Fejervari wasn’t competing to fit a ‘winner’s’ mold, instead, he presented his own artistry in a take it or leave it way. One of the riskiest choices a competitor in a competition makes is choosing their final concerto. How often do we see Rachmaninov’s or Prokofiev’s second or third concerto, or the Tchaikovsky first? The Rubinstein finalists all happened to make the safest choices possible: 3 played Rachmaninov 3rd, 3 Prokofiev’s 3rd. I say safe as in, you have the best chance to show off your mastery of the instrument. But Fejervari played Bartok’s 3rd in the finals—not an easy piece, but he had the added task of convincing the jury that this piece was worth competing with against the ‘war-horses’. (The last winner of the Montreal Competition won with Beethoven 4, an equally risky choice.) I’ve been skeptical of the propensity to see many of the same pianists sitting on the juries to multiple major competitions each year. I don’t blame jury members for accepting invitations, but why do competition boards continue to ask from the same pool of artists? If the goal is to find a young artist that stands out among the rest, you don't want the same crowd choosing that winner; inevitably the same jury members will choose the same kind of pianist. The issue of jury member’s students competing is another one, fraught with questions of correlation and causation along with competition rules that I’d prefer not to get into. It’s covered quite well in this article in response to Veda Kaplinsky and previous Cliburn competitions. The Cliburn has attempted to avoid these issues entirely this year. In the press release first announcing the 2017 jury and rules for application, they made note that only one of the competition jury had ever served before, and that the screening jury competition jury was comprised of entirely different people. They further made a brave attempt to avoid bringing teachers on to judge, focusing on (recently) retired professors and several artists who exclusively perform. From what I can tell, they were largely successful in avoiding student and teacher pairings among competitors and jury. Their focus clearly was on establishing a jury with a wide variety of unique, intentional artists and I expect that the eventual medalists will reflect this. I think it shows in the competitors chosen for the Cliburn, starting this week. They are from all over the world, and there is very little repetition among their place or professor of study. And their repertoire! Yes, among the concertos, we see the same warhorses: 4 with Prokofiev 2, 5 with Prokofiev 3. 5 with Rachmaninoff 3, and 7 with Tchaikovsky. But, 0 playing Rach 2! Among solo repertoire, only 3 offer Stravinsky’s Petrushka, and 4 Ravel’s Gaspard de la Nuit, two pieces I thought everyone tried to do at the last iteration. What about what’s novel? A few offer Beethoven’s 4th concerto, or Liszt 2nd, and each of Chopin’s are the ‘grand concerto’ choice of one competitor. There’s a few solo Messiaen offerings, Clementi, C.P.E Bach, a few Schubert Impromptu sets, and a variety of J.S. Bach, and several people offering contemporary composers such as Carter, Ades, Takemitsu, Corigliano, Rzewski and Auerbach, in addition to the imposed piece by Marc-Andre Hamelin. There are many examples of someone playing a less virtuosic or less known piece from a well known composer, say Scriabin (10th Sonata), Brahms (Op. 118), Prokofiev (4 etudes), Shostakovich (1st Sonata), Debussy (Reverie). And the sheer art of programming. So many competitors programs work against your expected programming of romantic repertoire with a nod to something a little more conservative, in the best ways possible. Two examples I’ll point you to are Luigi Carroccia’s entire program, and Dasol Kim’s Semifinal recital. So-I’m optimistic and excited to be bathed in piano playing. I will be posting reports every two days or so. I hope to not fall into the trap of being a ‘back-seat’ jury. I’m hoping to be so intrigued by all kinds of great piano playing that I can just wax poetically with optimistic fervor. I’m sure I’ll have my favorites and my least favorites, but more than anything, I expect to be intrigued, excited and inspired. Hopefully I can share that with you! A lot of studying the piano is learning to copy, from our youngest years through at least until completing undergraduate education. Initially, this isn’t a bad thing. We need models to learn:

But there comes a time that we want to move away from copying. Until we do, we generally only function as accidental, or perhaps unintentional, pianists. We’ve done everything by chance, regurgitating what we’ve learned instead of processing and adding value to everything we’ve been taught. Sometimes when we think we’ve gone off on our own, we haven’t actually done so. I’ve argued that the act of performing is at least as important as the texts on which our performances are derived. I believe our ears are easily manipulated by what we hear and most of our performance decisions are not truly our own; see case studies in Beethoven and Liszt. And so I’d like to suggest embracing what I have decided to call 'intentional pianism'. What makes a great pianist stand out? Our favorite pianists have at once a pianistic voice that is all their own, that sounds completely familiar, and simultaneously keeps us thinking and guessing. They’ve studied all the rules but have commanded the authority to break them. They have a sort of intentionality to the way they play music. All this is not to suggest that intentional piano playing is limited to the great masters. Some of my absolute favorite musical memories are from pianists who are not famous to the general classical music population. Some of the most distinctive performances I’ve seen were by students who brought an energetic commitment rare among artists, others are from professional artists who have sought their own career path, whether to pursue unique repertoire or venues for their performances. Anyone can play with intentionality. Nor do I want to suggest that our educational system is failing students. I’ve benefited from studying with an incredible, diverse group of piano teachers, all of whom are brilliant, and largely fall into the category of a ‘traditional’ piano teacher. And there’s nothing wrong with role of traditional piano teacher, in fact, traditions are essential. But to step out as performers with a personal intentionality, we need to use traditions as a stepping stone, not an end in themselves. Our professors in lessons and classes only have so much time to help us reach the level of being a unique artist. My goal with this blog and other future endeavors is to supplement the great teaching that goes on in piano lessons and schools of music. I believe some of the keys to being intentional include:

With this blog, most of all, I hope to outline how one can become a truly independent, a truly intentional pianist. Over the course of this next year, I’m going to present 5 blog series along with several standalone posts. First will be Extraordinary Recordings, a series studying several of my personal favorite performances on record, focusing on what makes the performer so unique. This will be, in a sense, a series of 9 case studies on pianistic intentions. Simultaneously, I will report on my viewing of the Cliburn Piano Competition, my favorite performances as well as thoughts on the repertoire chosen, and nature of competitions in general. What better way to ruminate on the state of intentionality than by studying this competition of world-class, young talent? Later on, with the hope of inspiring some summer reading, I will release a series of posts on Influential Books. Some of these will be explicitly musical, but several will be from outside the musical world. In the fall, I will be ruminating on the Coexistence of Contemporary and Traditional Classical Music. This will be in preparation for a project that I’m very excited about, which I will announce later in the summer. Finally to end the year, I will discuss my views on Performance Practice, especially focusing on my work studying the amazing pianist Ervin Nyiregyhazi. I hope you’re as excited about this journey as I am. Please subscribe to my e-mail list to the right, as I would love to keep you apprised as each new series is rolled out, as well as my projects as a performer.

Here's one more audioblog post where I introduce the main attraction, La Rousserolle Effarvatte, or the Reed Warbler. Be sure to check out this YouTube video to see the bird in action, and to compare its song to the interpretation in my performance.

A change of pace from the Messiaen...

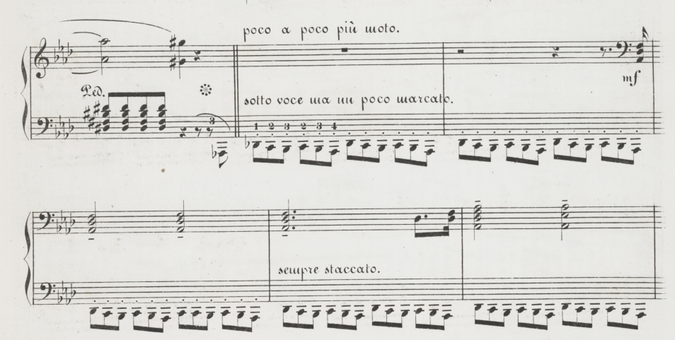

I have sat on this recording for almost a year and a half now. In general, I was not happy with this recording session and only had a couple movements of Mozart cleaned up to actually share publicly. But I’ve continued to think about this Franz Liszt run. It is messy in the beginning with a couple memory lapses but generally stays on track and presents how I’ve heard this piece in my head. But there is another reason I’ve always been hesitant to widely share my performances of this piece. I drastically depart from the standard performance practice in one notable area. Funérailles is famous for the middle section fanfare, the military parade which, as the route passes by the listener, the pianist explodes the thunderous bass ostinato with octaves. It’s virtuosic and may or may not reference Chopin’s famous A-flat Polonaise. Here’s the beginning of the section, from the first edition: Notice the tempo marking: poco a poco piú moto, or, ‘little by little more motion’ from the last tempo indication, which was adagio, in the very beginning. Other editions, including Henle’s Urtext, and editions by Emil von Sauer and Liszt student Jose Vianna da Motta agree. And YET no one plays it like this. At the beginning of this section, the second measure in the excerpt above, performers always take a new, fast, tempo. I’ve never understood this. Franz Liszt clearly marks a new tempo (Allegro energico assai) only at the climax of this section, and continues to reinforce the poco a poco piú moto until that point is reached. But performers always begin this section very fast. Are they afraid that they will not be fast enough by the time octaves are introduced and be accused of lackluster octave technique? Practice pacing yourself. You can start slowly but get to a tempo to leave no doubt in your abilities. You run the risk of the opposite problem: starting fast, and trying to get faster so that your octaves are doomed to fail. Even Horowitz succumbed to this extravagant failure and had to drastically cut the tempo back at the climax of the section. My performance of the military march here is an accurate depiction of this section, I think, and the effect of movement, the tension of the unyielding ostinato, and the pride of the moment is accentuated if this section begins adagio. It makes for a strong musical choice, but I have yet to find anyone to actually make this observation, whether in writing or in performance. Particularly listen to 7:00-9:15. The military march section begins at 7:25, the octaves at 8:30, and the Allegro energico assai at 8:50. What do you think? Give it a couple listens then tell me if you're convinced, or if you find the sudden tempo change a better choice. I'd love to hear from you! |

"Modern performers seem to regard their performances as texts rather than acts, and to prepare for them with the same goal as present-day textual editors: to clear away accretions. Not that this is not a laudable and necessary step; but what is an ultimate step for an editor should be only a first step for a performer, as the very temporal relationship between the functions of editing and performing already suggests." -Richard Taruskin, Text and Act Archives

March 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed