|

I thought that a good summer project would be to revisit some old performances of mine. The oldest recordings of myself that I know to be in existence are from my second year of my undergraduate studies. I haven't found the CD of that session, but I'm sure it's somewhere in my home. I do have my junior and senior recitals, plus several other recordings from my undergraduate years, not to mention all recitals I've done since, and non-recital sessions of other works too. I'm lucky that I've made sure to get decent recordings of almost all major repertoire i've learned.

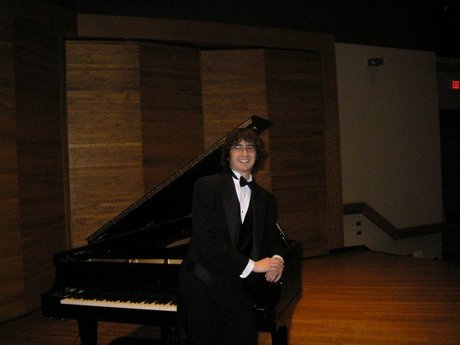

My memory would tell me that my piano playing back in the day was awful. I've improved technically since then, and clearly I had no idea how to listen to my own playing, interpret music correctly, or practice for strong, individual performances. As I listen back, I was actually quite wrong. I don't hate my playing from my late teens and early twenties. I hear problems in it, but I also hear an individualistic artistry which I recognize as an early version of my playing today. So I thought I'd share some old personal recordings and comment on them. First up is my Junior recital from January 19, 2007. This was my first full recital program ever, including Bach's Prelude and Fugue in D, WTC II, de Falla's The Miller's Dance, a couple Debussy Preludes, Morel's 2nd Study in Sonority, (maybe something else?) along with this Haydn Sonata. This date is the only time I ever wore a tux with tails, rented for the occasion, and for some reason, I thought so much hair was a good idea.

that one of my biggest issues was a tight hand and wrist, likely due to under utilized finger position, and poorly integrating all of my upper limbs. You can also hear it in the scalar passages like M. 36-37.

Some of the musicality is naive. You can count out all of the fermatas, they're far too unoriginal and ill-contrived. I would like to hear more detail in the articulations, especially a closer attention to slurs. A lot of "hits" are the exact same strength, i.e. M. 74, 76. But on the good side, I do back off for M. 78 to create a nice little line. There are other moments where I listen and match the tension and release of a line well, say M. 60-61 I really like how I listen to the ends of phrases; M. 4-5 and M. 6-7 make a nice pair, and M. 10 captures the confusion of landing on this strange chord really well. Overall, it sounds like I do get the jocular character of this piece quite well. I don't have all the tools to execute it yet, but I do hear something in my playing that I like, and I'm grateful that I had great teachers who heard it as well. In light of my last couple of posts about listening and recordings, I thought I would point you towards this interesting article I had on my 'to read' list for several months, that just happened to fit the subject perfectly. It's called "Learning from Listening" and the author holds some of the same opinions I do, and some differing ones. Taken as a whole, I thought it would be worth sharing several excerpts, annotated with some of my own commentary. There are many benefits in listening to the repertoire you are working on, on disc and in concert, as well as “listening around” the music – works from the same period by the same composer, and works by his/her contemporaries. Such listening gives us a clearer sense of the composer’s individual soundworld and an understanding of how aspects such as orchestral writing or string quartet textures are presented in piano music, for example. I've always had problems with "you have to", when it comes to interpreting music. As in, "You HAVE TO know the Beethoven quartets to understand his piano music" or "You HAVE TO know Schumann's love letters to Clara to play the Fantasy". In a blind listening, no one can say definitively that 'yes', I clearly know and understand Beethoven's late quartets. But I like this "listening around". Especially when it's expanded to other composers of the time period. Composers always notate their music with certain assumptions that performers would understand the written symbols. Seeing and understanding works of the time could give a fuller picture of what was implied or taken for granted in musical notation. Conversely, hearing a performance which I may dislike is never a waste of time. When I heard Andras Schiff perform Schubert’s penultimate piano sonata (in A, D959), a work with which I have spent a long time in recent years, I found myself balking at certain things he did to the music – not that anything was “wrong”, it was simply not to my taste. But one thing I took away from that performance was his pedantic treatment of rests in the first movement (Schubert uses rests to create drama, rhythmic drive and moments of suspension or repose) and this definitely informed my practising when I next went to the piano to work on the sonata. I confessed in my last post that I don't really care for Martha Argerich. Obviously, many people, including many musicians I love and admire, do care deeply for her music making. I don't necessarily dislike her music, and there are moments in her performances that I like but...On the whole her playing doesn't excite me. But I would be remiss if I ignored her completely. If great artists value her work, I should try and pinpoint what her attraction is to others, and perhaps add some lessons into my own playing. Just because I want to discover my own artistic voice, does not mean I'm excluding any opinions from outsiders! Most of us are limited by our own imagination, experience and knowledge and great performances and interpretations can broaden our horizons, inspire us and inform our own approach to our music. But listening at concerts, and particularly to recordings and YouTube clips does have its pitfalls too. There may never again be a time when performers will make a living off of recordings...But all the same, unless you are watching videos from an artist's personal page, or from the official page of a record label, please do not listen to recordings on YouTube. We want to ensure that videos are monetized for the proper people who created the content, and that is very difficult to do on YouTube. (My own videos have received copyright claims for being performances of Menahem Pressler, and Lili Kraus, and while I'm flattered, I clearly am not either). We can be sure that whatever money is coming in through streaming is getting to the right people if we use Spotify or Apple Music. Recorded performances capture a moment in time and while they can certainly inform our playing, they can also become embedded in our memory and may influence our sense of a piece or obscure our own original thoughts about the music. This may lead us to imitate a magical moment that another performer has found in a note or a phrase – a moment over which that particular performer has taken ownership which in someone else’s hands may sound contrived or unconvincing. What a magical way to say what I've tried to convey so often. Perhaps we can take general approaches to artistry, but not exact interpretations. But how often do we try to get inspiration from how someone else has interpreted a piece. Much better to focus on people as unique individuals, rather than gods of detective work. The other problem with recordings is that some performers may take liberties with the score to make certain passages or an entire piece more personal. This tends to happen in very well known repertoire, where an artist will put their own mark on the music to make it their own, while not always remaining completely faithful to the score. They might take liberties with tempo or dynamics to create a certain “personal” effect. Thus, some recordings may not truly represent what the composer intended, yet these recordings have become the benchmark or “correct” version. I suppose I have made similar arguments before. However, I don't like the term "composer's intentions" and always recoil when I hear it, no matter the context. In the New Year, I will deal with this term extensively! So when we listen we should do so with an advisory note to self: that recordings and YouTube clips can be helpful, but we should never seek to imitate what we hear. It is the work we do ourselves on our music which is most important, going through the score to understand what makes it special, and listening around the music to gain a deeper understanding of the composer’s intentions so that our own interpretation is both personal and faithful. And here we come rather full circle. I recently discovered the Mendelssohn Octet. What an INCREDIBLE piece of music. I don't know why I never listened to it, I've known about it for at least a decade, but just this weekend I decided to give it a listen. This music spoke to a part of my musical soul, and woke that soul up in such a way that I didn't want to play this exact music in particular, but I just wanted to make music. So yes, listen to artists that inspire you, listen to works of great composers, but have the right intention. Be inspired not to copy them, but to follow them in making beautiful, inspirational and artistic music.

Sometime in the midst of my master’s degree, after I had read Kenneth Hamilton’s After the Golden Age, I came up with a study that I think might demonstrate the effects that listening to recordings has on individuality in one’s artistry. At this point in time, I was very frustrated with the general state of piano playing. So many people seemed to love Martha Argerich, and I didn’t get it (I still don’t get it but that controversy is for another post). All this I ruminated on in my last blog post.

As I entered my doctoral degree, I thought I might have the chance to work the study into my program, but as graduate work goes, I got too busy, ended up going another direction in my research and lost the chance to have plenty of student pianists nearby to test my hypothesis. I thought it might be relevant to share the general outline of the study. Maybe someone will one day take it up and test it! The procedure is simple enough: have two groups of pianists, likely undergraduates though their technical capabilities by no means need be similar. Each group would be given a score of some obscure work, likely from the early classical period, with relatively intermediate technical challenges. The score would make no reference to composer or style. I would recopy the score on notation software myself and include only the essentials: notes, rhythms, tempo indication, and meter. Dynamics, articulation, phrasing, metronome marking would all be absent. The test group would be given free rein to practice and prepare the score for performance in a given time period. The only stipulation is that they may not consult with any other person in their preparation of the score. The control group would also be given free rein to practice and prepare for performance in the same time period. They also may not consult with any person in their preparation, but, they are given a recording of the score which they must listen to every day. In the recording, which I would make with an attempt to sound stylistically appropriate, they would hear distinct choices in terms of tempo, articulation, dynamics, phrasing, rubato, etc. All participants would, after the same amount of preparation, record a final performance. These recordings would be sent to adjudicators. These professional musicians would be aware of the score, plus an edited score representing the distinct choices I made in the recording. Adjudicators would be asked to grade how closely each group adhered to distinct, observable and (relatively) measureable interpretive choices in the recording. My hypothesis is that the control group would make interpretive choices similar to the recording, more often than the test group would. As my goal in the recording is to not make controversial interpretive choices, I suspect that students in the control group would, without realizing, adopt the logical interpretive choices that I had made. While the test group may also make several interpretive decisions similar, given stylistic conventions, inevitably, something such as exact metronome marking, or articulations in a melody, or dynamics, will vary given complete freedom. Upon further thought, it may make sense to make one controversial interpretive decision in the recording and see how many of the control group go along with it. Secondly—What I would include in the score could change. I think it’s important to have as blank a score as possible, so that people’s artistry would be observable on a nearly blank slate. Perhaps I wouldn’t even need a tempo marking, “Allegro” for instance. That would be one way to see who in the control group would resist the pull of recordings enough to question what they were hearing. For instance-imagine having no tempo marking for the opening of Mozart’s Sonata K 545, and hearing it played adagio. One could feasibly, if you never heard this work before, yet intimately understood the style, not question the choice of tempo at all. Thirdly, it would be interesting to run this study with proficient high schoolers making up both groups, as well as only graduate students, even run it with only professional musicians. Then compare the rate of variance at all 4 levels. What if, on the whole, the control group’s interpretations adhered to the recording at the same rate greater than the test group, whether or not we are dealing with high school musicians, or professional musicians? I think the results of such a study would be fascinating. None of this is meant to discredit professional musicians, or students. The simple aim is to observe the roots of our artistry, and to find one way of explaining how our general sense of style in interpretation might have a fundamentally different basis than that of artists when the composers of the classical canon were themselves writers of ‘new music’. I discussed my trepidation about being affected (or infected) by the sound of other interpretations in posts about Liszt and Beethoven. I fear making decisions in my playing that aren’t derived from my own authentic voice and so often I try to avoid listening to recordings of pieces that I’m working on.

But that’s hard to stay true to… I often want to check tempos that others have performed at, especially when the composer writes a specific metronome marking. Was anyone else successful at getting up to speed when I can’t seem to? I’m a Suzuki piano teacher and a huge part of our system hinges on listening to the pieces before learning them. Someone might say of my own playing “well it sure sounds like you’ve never listened to a professional pianist play this”, or put a nicer way, “perhaps you should listen to _________ or _________ for some inspiration.” No one has said the former to me, though who hasn’t heard the latter in one way or another? It has been suggested that listening to recordings is a source of information, a way to solve problems in interpretation. By not listening to recordings that others have done, I’m forsaking my duties as a performer, akin to not studying the basics of performance practice and historical styles. But who says those professional artists have the right answers? Nowadays, being so easy to put a recording out to the world, who even says these artists are truly professionals, or even artists? Besides objective, tangible things like tempo markings, areas such as phrasing, rubato and degree of articulation can and will vary from performer to performer, hall to hall, piano to piano. It’s the combination of these varying elements that gives performers their own unique voice. At some point, artists ought to be able to make these choices for themselves. There is a difference between listening to recordings by others, and knowing the performance style of the time a piece was written in. Very few would ever suggest I not do the latter, so if I do that well, why would I ever need the former? How am I to know if a professional recording I’m listening to has made intelligent decisions? As I’ve written before, this was one of my goals in pursuing contemporary music. There is great freedom in not having an aural basis to your interpretation, or I should say, an aural basis besides the one that you create for yourself. A piece rarely, or never, played by anyone else can be approached with a completely blank slate and who knows how varied the result might be when intelligent musicians approach a score they’ve never heard before. I had this experience recently, at a recital by pianist Angelina Gadeliya. Amidst a beautiful program with Bach, Beethoven and Liszt, she performed two works by Richard Danielpour, one of which was just commissioned by her, the other being his Piano Fantasy, a piece I have played a few times over the last 3 years. This was a sort of dream piece for me, a friend of Danielpour’s had introduced it to me in 2010 and I bought the score but between being intimidated by its virtuosity and not having a good program to fit it on, I only learned the piece the summer of 2014. It’s a gorgeous piece, a set of variations on a Bach chorale, and it has everything, an organ-like opening, a toccata, something of a nocturne, a fugue, and right near the end, the chorale itself, whose phrases are punctuated by various interruptions, and cloaked in a Debussy-esque harmonic aura. More than anything, it’s a true show-piece full of beautiful expression. I’ve only known of a few other people to perform this piece, and Angelina’s recital was the first opportunity I had to hear it performed live by another person. I hope everyone gets the experience at least once, to hear a piece you know so well, which you’ve only ever heard performed in your own voice, come to life by another person’s artistry. That may not always be a pleasant experience, but for me it was. Every artistic goal—the scope and large-scale architecture of the piece—that I have had in performing the piece was present in Angelina’s playing, yet clearly this was not an exact aural image of my own playing. It’s like if you had two canvases of the same pointillistic painting by Georges Seurat side-by-side; standing back ten feet, the images look exactly the same; when you stand just 5 feet away, you notice an incredible amount of variety as you see the construction of the dots more closely; 1 foot away, the paintings look the same again because you’ve zoomed so far in, it’s hard to compare individual differences. Examining the score from a distance, her interpretation and mine were relatively close to one another. Examining the score under a microscope, we played the same notes and rhythms. But our own voices came out upon that middle examination. More than one hears contrasts between artists in the standard repertory, not having any outside influences brought about a variety of musical decisions. The colors evoked by voicings in individual chords. The balance with a texture. The pacing of dynamics. The sweep of rubato. All this is not to say that I don’t hear variety between artists in standard repertoire. I do, and I love the artistry great pianists bring to old music again and again. But I know that without the persuasion of recordings, I am going to inevitably bring a different voice to music than I would with them. In my next post, I’m going to tell you about a study I’ve always wanted to do, where I think I could prove this point.

Initially, I may have been aiming to hide flaws in my playing. As I spoke of my undergraduate years inthe first blog in this series, my facility lagged behind my enthusiasm for the piano for several years of advanced study. Playing “standard” but rarely heard repertoire masked my flaws by its novelty. But as my technique improved, I realized another draw to this music: I didn’t like how many people played the standard repertoire. And if my own musical ideas weren’t widely accepted, I could at least more easily let my imagination run freely where few people knew the music. I had the good fortune during my masters degree to study classical performance practice at the modern piano. Experimenting with the fortepiano, even playing for the legendary Malcolm Bilson in a masterclass, opened my eyes to the fact that not all of our presumed traditions today are in fact what was intended by the composer. But it was Kenneth Hamilton’s After the Golden Age which truly opened my ears to a sound world, a style of playing, which truly felt natural for my own intellect and tastes. ---------- How do we know what a piece of music is supposed to sound like? Interpreting a piece of music requires a lot of assumptions, interpretational ideas that we take for granted. After the Golden Age challenges a lot of those assumptions. We often speak today of the “Golden Age of piano playing”, but when it comes down to it, we’re often not sure what that actually means. We fail to acknowledge that pianists of the time—say the mid nineteenth century into the early twentieth century—had practices and authorities that we don’t recognize today:

The character and legendary stature of Liszt, the performer and composer, looms large throughout the book. Hamilton’s goal isn’t to allow unfettered recompositional license when interpreting works of the past, but we shouldn’t dismiss unfamiliar performance traditions—those heard in plenty on the earliest recordings of pianists who were trained in the nineteenth century—as scandalous: Referring to the editor in lavish performance editions: "Nowadays we need not try to grasp Beethoven’s meaning while being verbally bullied by Bulow, or Bach’s while being harangued by Busoni. But we could, while not denying the indispensable value of the urtext back-to basics approach, also embrace a tolerant position and treat the later performance history of music as offering viable options to present and future players, rather than simply constituting a sad catalog of corruption.” (pg. 280)

After the Golden Age not only introduced me to new expressive techniques in my playing, but challenged my ears, and indeed my intellect, to reformulate how I approached piano playing. For the first time I listened to old pianists, students of Liszt, and was amazed by what I heard. Their playing sounded original, the pieces I thought I knew inside and out felt brand new, the boring phrases sprung to life. My imagination was fueled, wondering what Liszt or Chopin would have sounded like themselves, cherishing this aural link to classical music masters.

And this book ignited a youthful, and sometimes misguided, passion to be different. So while Hamilton fueled my love for piano music from the nineteenth century, he also pushed me specialize in music from the late twentieth century as well as the modern day. My primary reason for attending the doctorate in Contemporary Music at Bowling Green State University was not primarily for the love of new music. Though I grew to cherish new music, I first and foremost wanted to develop my artistry in a body of repertoire that did not have an established performance tradition. The resistance to the traditions illuminated in After the Golden Age taught me to place myself in a position similar to these old piano recordings that I loved. By working with living composers, I could be an active part in the creation of musical masterpieces. In building an authority in this way, I hope to justify my playing upon my return to the traditional repertoire…But more on that in the fall! **This post contains affiliate links. While I may receive a small compensation if you purchase any of the products mentioned, the words used to promote them are completely genuine and offered regardless of any personal earnings**

But this follow-up I disagree with: “he somehow obliterates his own enormous musical personality by his occupation of the territory of the author he plays.” I’ve never done a blind test, but I would wager that I could tell Sokolov apart from other pianists if I did. It’s precisely because his musical personality shines through the notes left by the composer that I enjoy his artistry so much. He has a unique gift to reconcile a composer’s voice with his own.

And then one more statement I do agree with: “Sokolov’s first concern is always his relationship with his instrument.” He is first and foremost a pianist, in the best sense possible. He knows how to express music through the piano. It’s well known that Sokolov doesn’t collaborate, whether in chamber music or concertos, at least not anymore. He’s often said that it’s too difficult to find a musical partner with similar musical sounds, not to mention, the economics of rehearsing an orchestra long enough to have a unified musical message. So he plays solo piano, exclusively touring Europe with one program each year. Clearly he gets to know his program so well that once he’s performing publicly, he knows exactly how to make his music heard perfectly. But that requires the perfect instrument. Sokolov is also known for working as his own piano technician. Spending hours alone in the concert hall before a recital, he will adjust the piano so that it responds exactly as he would like it to. That might sound like ‘cheating’, manipulating the playing field so that he’s always playing with home-field advantage. But if you make that much effort not just to understand the technical work of adjusting piano mechanisms, but to know exactly what you want out of an instrument, why not utilize it? So he’s truly someone engaged with what a piano is capable of musically, chooses a program which engages the piano best, and masters the small repertoire to create incredibly moving performances. To go a step further, all of his commercial recordings are live, unedited recordings. I don’t know if he’s ever stepped foot into a studio or had an audience hear a recording of his playing that was spliced together from multiple takes. It was difficult to decide what recording to focus on, but I decided to look at Chopin’s 2nd Sonata, Op. 35. Chopin, being a pianist’s composer, and Sokolov, being a pianist’s pianist, sounds like the perfect combination. Chopin of course took ample inspiration from the world of Italian bel canto opera, and wrote in such a way to best approximate the singing style on the least-singing instrument. The best Chopin singers surpass the piano’s percussive nature to create the impression of singing legato with the requisite balance of phrasing, dynamics and rubato. I’d like to suggest that Grigory Sokolov is uniquely qualified to find this balance because of his total engagement in the piano as an instrument. Of course he sings throughout the first movement. The left hand is not overwhelming in the opening agitato theme and his nocturne impulses shine in the secondary theme. The second movement is as playful as the music allows, making the most of the changes of register, and the motivic repeated notes are never hammered. In the famous third movement he acquires the necessary bleak character, and even manages to make the piano sob at the sforzandos, or the left hand trills in the march section. He makes sense of the strange finale by adding color with the pedal and draws our ears closer by alluding to motives in his voicing. I’d like to look most specifically at one spot in the Development section of the first movement, M. 137-153, heard at 5:24 of his recording. Here the agitato theme in the right hand is combined with the opening descending sixth octaves in the left hand. If you listen closely, there’s a slight hesitation in the right hand to give a moment longer to listen to the left hand. In that way, the left hand sounds full in tone because the sound has a moment to bloom, and we get to listen to the combination of the two themes. Without that regular hesitation, the piano would sound completely homogenous, instead of heterogenous. Sokolov understands and hears how the sounds he makes at the piano will be perceived at his attack, and exactly how it will decay, and he manages every other musical decision around those basic realities. And because he works so closely with his instrument at each performance, he is able to guarantee the response that he wants. In this way, Sokolov ismuch unlike Glenn Gould who prized structure over the sound.

For me, her Mozart—like many other pianist’s—is too neutered: the left hand too insubordinate and dull, the slurs smoothed over. Uchida said in an interview that she would love to express what’s ‘inherent in the score’, but says ‘it’s not possible’. We are too influenced by our culture, our upbringing and our listening to other artists. I couldn’t agree more on the latter point. It just seems that she focuses too much on the score in Mozart. (I wonder if that was a younger Uchida.)

Her unique upbringing will inevitably would have led her to hear music differently. She often states that growing up in Vienna influences her connection to the music of great Viennese composers. She describes her ideal approach to musicality another wayin a more recent interview. Uchida says that she tries to approach each composer and each piece, with a blank slate. Her work, whether privately in practice or publicly while in performance, is an attempt to discover the music without outside interference, or even from yourself and the way you did it the day before. Approaching music this way we will inevitably strike a balance between performance traditions and our own honest musical selves. Schubert is of course best known for his composition of lieder, revolutionizing the art song with piano accompaniment. Whether it be for allowing the text to guide the composition, or for including the piano as a collaborative element, more than accompaniment, his vocal works are rightly celebrated to this day. I think the reason I love Uchida’s Schubert so much is that she sounds like she’s playing lieder. Coupled with the blank slate approach, and her playing begins to take on qualities of storytelling: always fresh, always vibrant. Schubert in her hands sounds like long narrative songs without the words. I’d like to focus on her performance of Schubert’s second-to-last Piano Sonata, the one in A major, D. 959, although her complete Schubert set is worth listening to extensively. The first movement begins full of majesty. Each new harmonization of the As in the right hand have a color and direction of their own. Her left hand continues its active role in measures 10-13. Try isolating your listening to only hear her left hand. There is so much shaping there, an entire phrase, even though it is the background texture. The transition from measures 28-39 has so much drive, it sounds like she’s accelerating, but check a metronome and she’s staying unusually steady. I think this phenomenon has something to do with the crispness of her right-hand articulation. She slows down the tempo for the second theme, even though it’s unmarked. I discussed the need for this in the previous entry in this series. Uchida herself has an interesting discussion about tempo in the Steinway interview linked above. She says that a metronome marking could be perfect in one performer’s hands, horrible in another’s, depending on what else they do with the piece. There is no right tempo. This seems intuitive of course, but why shouldn’t we intentionally apply this concept to individual musical themes? Especially in a single Sonata movement, where the form often pits two contrasting themes against each other. This choral is where we first hear a truly song-like melody. She plays it very simply at first, from measures 55-63. When that melody is developed starting in 65, her tempo is again largely the same, but he addition of the left-hand accompaniment creates a greater sense of motion. Not only that, but the left hand is shaped such that the eighth notes on beats 2, 3, and 4 are voiced as a countermelody to the soprano voice. If the whole pianist is a collaborator in lieder, the left hand must be the collaborator in the piano sonatas! To hear a great lieder-like collaboration between her left and right hands, look no further than the beginning of the finale. The right-hand sings impeccably while the round shapes of each half note space in the left hand follows the rise and fall of the melody’s phrasing. Even though I like her shifts in tempo, I am most amazed with how steady she is between tempo changes. Yet it doesn’t sound steady in a perpetual motion sense. Her control of her sound to make a phrase is something to behold, study and be inspired by. Sound influences time so much in her hands, and as someone who allows time to control everything in my own playing, I am enamored with this skill when played with Uchida’s perfection. A final interesting thing to note, since I criticized her neutralization of slurs in Mozart, is her voicing in measures 90-105 of the finale. Since no slurs are present in the urtext edition, most people would likely play the right hand as one steady voice throughout this section. Uchida turns the right hand into a duet. A lower voice in 90-93 begins, then is interrupted by a higher voice, the upper octave that measure and the next. Then the two voices trade off beats 3 and 4 of one measure and 1 and 2 of the next. It’s a minor detail, not brilliant save for the fact that, by making a choice of voicing the right hand slightly differently, a textural dialogue that is absent in the score, is discovered, magnifying our listening to the piece. Day 8

A quick rundown of the Mozart concertos: not a lot of variety here. 6 competitors will play the d-minor. Will any take a big risk and not play the Beethoven cadenza in the first movement? No. 21 in C major is chosen by 4 competitors, and there is no historical favorite cadenza here which could be fun. The 2013 winner, Kholodenko notably composed his own cadenzas for this concerto, allegedly on the plane to Texas. Number 23 in A and No. 25 in C only get heard once. Looking ahead, the final concertos have broken down quite nicely. Most popular is Prokofiev 2 with three competitors, Tchaikovsky 1, Prokofiev 3 and Rachmaninoff 3 each have 2 competitors. Then if we’re lucky, we might hear as many as 3 amazing, but atypical final concertos: Beethoven 4, Liszt 2, and Rachmaninoff’s Paganini Rhapsody. ---------- Daniel Hsu begins the Semifinals with two of my absolute favorite pieces of all time: all 4 Schubert Op.90 Impromptus and Brahms’s Handel Variations. You might say these are two of my dream pieces. I was so struck by his Op. 90/2. Often played as a perpetuum mobile, Hsu found shaping in both parts. In the fast A-section right hand triplets, he made melodic phrases with his dynamics but also with subtle shifts in time to give the sense of breathing. But his left hand chords were integral too; if we could just listen to his left hand alone, we would still hear beautiful music, not the most interesting music for sure, but as musical as any performer could make it. Each chord had its own unique role in the harmonic progression, clearly heard by Hsu’s shaping of the whole phrase. I also loved how much he utilized asynchronization of the hands in the B-section to promote its angsty character. A little detail in number 3 that I loved was that he treated the first two measures as one phrase, then a second phrase beginning in measure 3. Often we hear one continuous phrase, though the Gb in measure 2 is clearly meant in the score as the end of a sentence; at least a semi-colon if not a period. One reason I love the Handel Variations is that Brahms takes one element at a time from very blah theme and transforms that element into something ingenious. This is opposed to re-writing the same variation, altering it slightly each time, the more classical approach that Handel himself takes with this theme in the original keyboard suite. Brahms’s genius as a composer is never more clear than in this work but it is also a chance for the pianist to show of different sides of their personality. A second reason is that there are so many opportunities for the performer to showcase their own intentional creativity by bringing out different elements in each variation. It could be a different voicing, phrasing, rubato. Given this, even on playing the literal repeats in each variation, the theme continues to evolve. In a sense, there are many more than the 25 numbered variations, so long as the pianist seeks them out. I would say Daniel Hsu did just that. ---------- Way for Dasol Kim to make this Mendelssohn NOT all about the dense, active notes Mendelssohn has given him. Fantastic control of the finger work, relegating it all to the background. He has plenty of fantasy to live up to the name, every section comes alive in its own right before something else takes over. Kapustin looks strange on the page against Mendelssohn and Schubert. But that might be the point-to show his versatility as an artist. This programming is to make a point about Dasol Kim the pianist, not to make a point about any of the music, which I’ll give him props for. Schubert Sonatas are a tough competition sell: the virtuosity isn’t the easily visible or audible kind you get with Liszt, Rachmaninoff or Prokofiev, But it’s incredibly virtuosic music in its subtleties and pacing and nuances. All the more so in this last Sonata, it’s so long, so exposed, if you aren’t in total control of what you’re doing, you’re sunk. Dasol Kim isn’t sunk. His control over the melody is beautiful, and while I’ve heard more organic rubato, dissolving a sense of time in this first movement, he keeps the piece interesting, the pacing never bored. I especially love the first and second movements when one takes a very slow tempo, just to enjoy every moment, every beautiful harmony, every gorgeous melody. But that’s so hard to do, and he’s on a time limit. I’d like to make a quick note of his 4th movement, the one that’s always hard to process after the profound first and second. He doesn’t treat this movement too much like a joke. Even though the main theme is very light, and he plays it very laid back with some beautiful rhythmic nuances, Schubert still wrote plenty of drama, especially in transition sections and Kim makes the most of that I never thought a lot of Dasol Kim after his first recital, but I could not think much more of him after his second and confirmed now with the third. Day 9 Beethoven’s 26th Sonata, is another piece I get tired of, since it’s a very popular student piece. There’s little worse than hearing those first 3 right hand octaves of the fast theme in the first movement pounded out equally, without any direction, or same thing with all of the running doubled notes. It’s hard to play and hard to play musically. Even if he didn’t sell me on the first movement, Yutong Sun avoided these student sounds. I was intrigued by his exuberance in the finale. The outbursts of sound represented the joy of ‘the return’ that I hadn’t considered before. And then there’s Liszt’s Un Sospiro. At one summer festival I attended, at least 5 people played it, 2 faculty and several students. I’m not sure I’ve heard it in 7 years. And I didn’t really mind his performance. He had some nice interaction between the shaping of the melody and shaping of the accompaniment. Then he went attaca into Pictures at an Exhibition. Later, webcast hosts Anderson & Roe doubted the connection, after all, isn’t Un Sospiro about love, Pictures about friendship? Apparently the Liszt title didn’t originate with the composer, plus the set of etudes are dedicated to his uncle. Perhaps we can agree that both pieces are about a kind of love, perhaps romantic, perhaps familial, perhaps fraternal. It’s hard to know what to say about a piece such as the Mussorgsky, in Sun’s hands. Easiest to say I loved it throughout. This is not a pianistic, lies awkwardly and doesn’t always utilize the instrument in the best way possible, which is why the Ravel orchestral version is so popular. But I’ve always loved the piano version best, and it’s because of performances like this. Just listen to his Great Gate of Kiev, even with natural piano decay, the gigantic chorale chords never sound like hammer blows, something more like an organ. It takes great artistic listening, total engagement with the sound you’re creating, to make such beautiful music out of something so vertical. ---------- It’s surprisingly that more people don’t play the Vine Sonata that Honggi Kim did...Until it becomes standard, it can help define your credibility with an often ignored segment of the repertoire, and it clearly shows off your chops, and the audience will enjoy it’s irregular meters. I heard a convincing performance if Kreisleriana earlier this year, but this is a tough piece to pull off. It’s long, and it’s Schumann, meaning you’ve got to do a lot more than play the notes. For me, Kim didn’t do enough to differentiate the monotony making the piece feel longer than it needs to be. ---------- It takes guts to program the Hammerklavier. It worked for Sean Chen in 2013, and you have to assume he serves as the inspiration for someone like Yuri Favorin. I’m less confident it will serve him well. His opening tempo was about 75 BPM and the whole movement had a rather languid moderato rather than a spritely Allegro (to compare: Sean Chen opened at about 100 BPM, still not close to the outrageous Beethoven marking of 138, but a lot closer!). Favorin clearly had control on this Sonata but you’ve got to give audiences a reason to care about this piece, and I never really heard it. I’m very interested to see if Favorin moves on. Of course, I love unique programming, but of the three solo rounds, Favorin played entirely obscure works by well known composers, save for the Rachmaninoff Corelli Variations, not to mention a strong Russian bent. At some point, you look at some members of the jury as performers, thinking about the kind of music they play, deciding who will represent the Cliburn going to forward and have to think they would hold this against him after a while. Especially in light of the many other competitors giving completely masterful, unique, intentional, performances of very standard works. I do love that he played the Shostakovich Sonata and would say this was his best decision. It’s a very strong work and unconsciously ignored by most performers. ---------- Schumann’s late works rarely get played, especially by pianists, ESPECIALLY in such a venue as the Cliburn competition. I’ve always enjoyed the Forest Scenes, and am so glad Tchaidze chose to program them. Perhaps some of the most romantic works that Schumann wrote, the searching, the painting in these pieces provides the perfect miniature opportunity for a pianist to showcase their artistry. Medtner is slowly getting his due from performers, although this is the only time in the Cliburn this year. Contrasting programs indicated that Tchaidze would play the actual Sonata, or the throwback piece at the end of Medtner’s Op. 38; the latter, full of sentimental nostalgia, was correct. I love this piece so much, though I love it even more when paired with the Sonata itself. (pro tip: there’s a video on YouTube of Vadym Kholodenko playing this as an encore after a concerto). His Mussorgsky was equally gratifying. Some interesting pauses in Baba Yaga which allowed sound to travel and the music to breath. The main theme of Great Gate of Kiev was the opposite; full of majesty, it ploughed forward. But the contrasting sections did just that, they were moments of reflection or repose. This is definitely the first recital of Tchaidze’s that I really took notice of, and I can see why he’s in the Semi-Finals. Perhaps I’m partly biased just based on the repertoire. But he had beautiful sound, and played with such romanticism throughout that I couldn’t help listening more closely than I had before.

She concertized as a young woman around Europe, but settled to raise a family, continuing performing during World War II. Moving to the U.S.A. after the war, she never gained a significant performing career, even though at her age she still played with impeccable technique and musicianship. The recordings we do have from her exist from this late part of her life. (See this website for my sources, and more, on this incredible life story.) Typically I believe in supporting artists by, at the very least, streaming their recordings from legitimate services like Spotify or Apple Music. Unfortunately, most of Freund’s recorded work is unavailable anywhere, even secondhand CDs. YouTube is the best way to make her art visible. I’d like to continue my focus on Brahms. Seeing as how he adored Freund’s playing, it is noteworthy to hear her approach to his music. What old performance practices, perhaps things decried today as outlandish techniques, do we hear from this legitimate, audible record of the composer’s intentions? To see, let’s briefly walk through just the first movement of Brahms Sonata No. 3 in f minor, Op. 5. My hope is that illuminating some of the techniques in her performance will give you a greater appreciation for her extraordinary intentions in music making. This is quite a different approach than I took in the first post about Glenn Gould! I’d recommend listening to the first movement in its entirety with the score, read my post and check out the specific spots, then take some time to listen to the Sonata in its entirety, perhaps without the score. You’re in for a treat! Significantly, throughout the performance, we hear plenty of unmarked arpeggiation of chords, or anticipation of the left hand. These unmarked forms of subtle rubato are so common amongst early recordings by pianists trained in the 19th century and are so often vilified as ‘sentimental’ today. You can’t perform asynchronously what is marked to be played synchronized! And yet, they do. Consider measure 7, (hear it here). Asynchronization of the hands is tricky to hear, so much that you probably need headphones on to hear it properly, but the left hand is slightly agitated, often anticipating the right. You’ll also hear this technique in nearly every lyrical area. Consider the second theme in the first movement (measure 39). The left and right hands are so asynchronized that one would almost hear this as Chopin. Often times these techniques are closely related to polyphonic playing. Pianists create more layers by arpeggiating or asynchronizing the hands, allowing our ears to catch up to hear melodic lines that we otherwise would not be aware of. In doing so, the harmonic structure and natural counterpoint is laid so much to the fore. Freund is incredibly sensitive to the polyphony Brahms himself wrote in. Consider the c# minor section of the development (heard hear). Each voice is matched perfectly to itself, and balanced with each other so that the canon is easily audible. At the same time, the general harmony of the phrase has drive and direction. Contrast that with the searching melody which happens at the key change to 5 flats. The syncopated right hand chords are played as triplets, rather than eighth notes but this lilt provides rhythmic anticipation which suggests the harmonic stability is an illusion, pointing us towards the true, unstable, development which will break out momentarily. Consider her tempo. The first movement begins at a quarter note around 70. The second theme is actually played faster, beginning in the 80s and accelerating (even before the un poco accel) to the 100s. I’ve heard it argued that all tempos in such classically minded composers must “live under the same roof”, that is, to be very closely related to each other, considering that they share the same foundation. I’ve also heard it argued “you don’t feel the same in the living room the same way you do in the kitchen or bathroom!” Freund, and pianists of her generation seem to feel closer to the latter: themes have their natural tempo which must be taken to promote the true character. The un poco accel at the ended of the exposition are treated as significant events, there’s nothing ‘little’ about them! Furthermore, they are more a sudden change of tempo, rather than gradual. But she slows down significantly for the cadences, especially the final resolution on the repeated Db major chords. She’s extremely mindful of the structural significance of every measure she plays. Listen to the last 23 measures (heard here). This is the first theme heard in the parallel major, and the tempo is just a little faster than the opening of the movement, mid-80 beats per minute. The Piu Animato jumps to nearly 100 beats per minute, which is fair enough. But the hemiola section 5 measures later is suddenly at 170, without provocation. Would you have noticed that if I didn’t point it out to you? I’d wager you wouldn’t, and that’s the key. Unless you’re counting along with a metronome like I was (for analysis purposes!), you aren’t consciously aware of these vast changes of tempo. Our primary focus ought to be on the transformative artistic picture which she is creating. The tension her changes of tempo create are more important than the means used to create the tension. I’d like to point out one more minor detail which sets mature artists apart from mortals like myself. In the development, 8 measures before the key signature returns to 4 flats, the left hand begins with a dotted sixteenth, 2 thirty-second note rhythm (heard here). She voices the thirty-second notes very clearly, instead of throwing them away. In fact, it’s almost like the first short note has a slight accent, which typically is a big no-no. But she has a specific reason for paying attention to these short notes: in the fifth measure of this motive, the thirty-second notes are followed by an eighth note, jumping up a tenth. Given her attention to the short notes preceding, we can hear the stretch of that interval. It sounds like one voice, where as so often, this motive sounds pointilistic, like two different instruments, which given Brahms’s phrase marking, is not the intention. On a closing note-there are several other Etelka Freund performances out there, other Brahms and a few other composers including Bach, Lizst and Bartok. Check them out. They all sound like Etelka Freund, which is a mighty fine accomplishment. If we inevitably are influenced by music around us, as I will always argue, we’re never going to present a sound authentic to only the composer. Rather than sounding like a neutered version of someone else’s impression of the composer, we might as well make an intentional effort to sound most consistently like ourselves.

Chopin is a composer ultimately focused on sound and poetry. Gould is a performer ultimately focused on structure.

In this latter approach, the composer doesn’t matter so much as the construction of the piece. How the notes were put together mattered more than the sounds they made, perhaps in the same way that a building would be judged whether it was functional, not how it looked. Says Kevin Bazzana in his book Glenn Gould: The Performer in the Work, ““Gould was concerned with musical expression but was motivated by musical structure.” (page 13, first emphasis mine, second in the original) The function could be innovative, but only because the structure first and foremost, was. Bazzana quotes fellow Bach specialist Rosalyn Tureck as saying: “In Bach’s music, the form and structure is of so abstract a nature on every level that it is not dependent on its costume of sonorities. Insistence on the employment of (period instruments) reduces the work of so universal a genius to a period piece…In Bach everything that the music is comes first, the sonorities are an accessory.” (page 21). This universality is essential, I think, to understanding Glenn Gould’s performance. It is a universality which truly opens the performer up to playing with extreme sensitivity to musicality and expression that’s inherent in the work. That sensitivity may not be inherent in the standard practice of a piece, thus we get to hear Gould’s unique style of playing (see his recording of Beethoven’s final 3 Piano Sonatas for an example of something strange that, I believe, ‘works’). So Gould, “could ‘let loose’ in performance only with music whose structure met his standards of idealism and logic, music that he could first justify rationally.” (page 35) Chopin, not focused on structure will never sound truly revelatory and natural in someone like Gould’s hands. And that brings us to Brahms. Glenn Gould recorded 10 Brahms Intermezzi early in his career, in 1960. (Later in his career, indeed one of his last recordings, he also recorded the Op. 10 Ballades and the Op. 79 Rhapsodies). These Intermezzi, I do believe, constitute the most perfect musical recordings in existence, and they are often overlooked in Gould’s output. At first, Brahms seems not the quintessential Gould composer, especially given his controversial performance with Leonard Bernstein of the first concerto. But when we remember Brahms’s classicist bent, his love of Bach and Renaissance polyphony, his dedication to absolute music, it makes sense. These short forms (as opposed to the earlier Brahms Sonatas and Variations which Gould decried as “pianist’s music”) fit his temperament perfectly. On these pieces Gould himself says, “I have captured, I think, an atmosphere of improvisation which I don’t believe has ever been represented in Brahms recordings before…total introversion, with brief outbursts of searing pain culminating in long stretches of muted grief…” Or, in his words, these are the ‘sexiest’ recordings ever made (these quotes from the liner notes of this other volume of the recordings). Call it sexy or not, the Intermezzi are performed with incredible attention to expression of the melodic line, harmonic shaping, rubato and structural drama. Given the way he shapes and connects melodies or layers the polyphony, I truly believe that Gould could hear with better detail than a typical musician. Like Gould’s Bach, every line in these pieces sounds independent and musical. I point your attention to the counter melody on the repeat in the B-section of Op. 118 no. 2 and when the melody returns in the minor a few phrases later. I hesitate to analyze much further because of the perfection I hear, these recordings just speak for themselves. He has a way of balancing different lines to make us listen to something different every few measures, without losing what we were listening to before. He magically forces us to listen polyphonically. Clearly Gould was not a dry, mechanical performer, but was capable of intense romanticism in his playing. We hear it clearly in these Brahms recordings, evidently just because by looking at the structure first, he could see the beauty inside the functional, rational architecture that he simply doesn’t see when the elements are reversed in something like Chopin. |

"Modern performers seem to regard their performances as texts rather than acts, and to prepare for them with the same goal as present-day textual editors: to clear away accretions. Not that this is not a laudable and necessary step; but what is an ultimate step for an editor should be only a first step for a performer, as the very temporal relationship between the functions of editing and performing already suggests." -Richard Taruskin, Text and Act Archives

March 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed