|

This past year I learned and twice performed Beethoven's Variations and Fugue in Eb, Op. 35, commonly known as his Eroica Variations, as the theme of the variations is the same theme as the finale of his 3rd Symphony, also titled Eroica. This was never a dream piece of mine per se. A friend of mine had played it in our undergrads, and I heard Jeremy Denk do it live once. But it's not a piece I knew much about, nor one that I could "hear" in my ear (besides the theme). I knew it existed, but beyond that, my mind was a blank slate.

So last summer, I decided to learn it, and keep my mind free of the interference of other interpretations. (I discussed the problem of being influenced by recordings in my Artistic Messages blog series last fall, particularly #4.) I thought this would be an ideal piece to see exactly how much my artistic voice would differ from that of others: this is a significant, virtuosic piece by an iconic performer, but one relatively unknown to most people. While learning the variations, I listened to just a couple people start the fugue to get a sense of their tempo, that's it. I didn't listen very long, and I tried to ignore all other details of their playing, beyond what I needed to satisfy my discomfort with my own tempo choices. Otherwise, to this day I haven't had any influence from other recordings of this piece. (Though full disclosure, I have played this piece once for my former teacher Thomas Rosenkranz, and twice for my coach Louis Nagel. Both mentors gave invaluable help and advice, yet neither works with me in such a way as to fundamentally change my interpretations. I see their influence as clarifying my vision of the piece or helping me reach that vision more efficiently). Here's the very first performance of that piece, from my Choosing Joy recital in February.

Bass plus one voice: 1:20 area-I debated a lot whether to bring out the bass, or the 'new' section-the duet. Here I'm not consistent enough with either, though I do like bring out the difference: the duet.

Bass plus two voices: 2:10- I like the dialogue here! Bass plus three voices: 2:45- I had a memory issue of a different variety in my 2nd performance of this piece too. Theme: 3:25-I'm pretty happy with the phrasing here, though some of the passagework needs cleaning up. You need this jolly feeling here, but the arrangement and texture is really heard! Variation 1: 4:05- It's so easy to over rely on the pedal here, but I'm glad that I'm not! Variation 2: 4:45- of course Beethoven would make one of the hardest variations the second one. I'm quite happy with the tempo and cleanliness of the A section especially. I don't love arpeggios, but am glad it's in the key of Eb, and not C or F#. The mix of black and white notes helps a lot. Variation 3: 6:09- there's a really tiny memory slip I'm proud to have played through. Variation 4: 6:30 area- I've debated about playing different tempos in these variations, even with such consistency in sixteenth notes in these first four. But it seems to me they're so completely different in character, that I just need to "help" their differences a little bit. Variation 5: 7:05- Tempo especially different here, I want to milk these juicy intervals in conversation. Variation 6: 8:00- Just the week of the performance I was having major memory problems in this variation, so I'm glad I rectified it here. I'll take some unclean broken octaves instead. And again, success in not over-relying on the pedal. Variation 8: 9:20- A precursor to Waldstein Sonata's finale. Everyone kept telling me to use more pedal here. I like the sound, but maybe will experiment with going further in this direction. Variation 9: 10:08- for me probably the 3rd hardest variation. Playing these chords, with such short articulation, but still making them beautiful. Not a very successful performance, though the B section was better than the A. Variation 10: 10:50. Actually one of my favorites. Besides the false, I like how it went. I'm trying to displace the meter as much as possible, each hand disrupting the other. Variation 11: 11:30 ish. Another favorite. Such a mundane melody, simple accompaniment. I actually had a lot of memory problems in the B section while learning it. Variation 12: 12:20- I guess tied with 9 for the 3rd hardest variation. My hands don't like to adjust to new hand positions so quickly, but then to play broken chords too, this could have gone worse. Variation 13: 13:06- it's up for debate whether this or #2 is the hardest variation. I'm still not convinced about how to use the pedal here. I'd take this kind of accuracy; I only completely missed the right hand note once, and a couple other times it was a little messy. I could have slowed down a tiny bit more and no one should complain, but gosh I really want to keep the energy going like I did here. Variation 14: 13:45ish- I wish I'd changed the mood more here. This should have been slower. But I like the voicing, and how I hold onto dissonances. Variation 15: 14:42- Very hard to memorize, and to phrase. And to count. I think I found a nice balance in the A sections between the short phrase articulations from Beethoven, but still maintaining a longer line. Fugue: 20:19- There's nothing so intimidating to me than performing a fugue from memory. My Master's recital had 3, including a 5-voice fugue. Listening to it now, it's been nearly 4 months since I last performed this piece, and I've read through the fugue maybe once or twice. It feels like a foreign piece! I can't 'feel' myself playing it as I listen, as I can with most of the variations. I'm impressed with the speed I have here, but I'm worried that relearning it is going to be very difficult! I'm very happy with a lot of the voicing and articulation, and besides a couple slips, the memory is quite good. This fugue is also difficult because it's so easy to play it all fast and loud. You want the feel of eroica, but without banging. Pacing is so important, and I feel like my performance doesn't get monotonous. Post-variation 1: 22:42- I never feel like I have great trills, but I really liked the sparkliness of those at 23:27. Post-variation 2: 23:38- My left hand melodic chords get very rhythmically monotonous, every repetition of the rhythmic device gets the exact same stress. When my right hand moves to 32nd notes at 23:53, I like the phrasing of the left much more. Overall, I like this performance a lot more now, than when I did a couple of weeks after it happened. I think I capture the distinctiveness of the variations so that this doesn't feel like a long piece. There's enough sloppiness that I'm eager to fix and it's nothing that a 3rd and 4th performance of the work won't fix!

His discography details an intentional identity. Two volumes of Scarlatti Sonatas, a volume of Haydn, collections of Scriabin and Chopin, along with concertos by Tchaikovsky, Medtner, Scriabin, and Rachmaninov (choosing the rarely heard original version of the 4th concerto, itself already obscure). Even in a solo volume of Rachmaninov, Sudbin plays the less famous Chopin Variations, instead of the better known Corelli Variations to couple with the 2nd Sonata. Sudbin (with the exception of Medtner) plays the most standard composers, yet he tends to champion their lesson known works with equal vigor as the masterworks. In the famous pieces such as Tchaikovsky’s first concerto he manages to find his own voice.

There is something to be said for forging your own path. Sudbin said that he not only began playing, but also improvising at the age of 4. He still does his own arrangements, often song transcriptions for solo piano. Beyond that, Sudbin is an active writer on music. All of his recordings that I’ve perused have been accompanied by his own liner notes which provide historical context and clues to his interpretations. In all ways, Sudbin takes an active part in the creative process. I decided to focus on Sudbin’s Scarlatti recordings, in particular the C Major Sonata K. 159 from the second Scarlatti volume in 2016. In the liner notes to the original Scarlatti recording, Sudbin describes the draw to Scarlatti’s oeuvre (he also reveals-unbeknownst to me, that Scarlatti’s 555 brilliant sonatas were only begun when the composer was 50 years old!). He says that Scarlatti’s compositional voice stands alone in music history: there is no distinct, singular origin or contemporary parallel. Of course, to come to this conclusion, one need only compare Domenico’s keyboard works to the vocal works of his father to see that little musical genetics were shared across generations. Furthermore, Scarlatti wrote these Sonatas protected and perhaps isolated by royal patronage, which in my mind elicits comparisons to the future works of Haydn: “Probably because he (Scarlatti) composed all of his sonatas for the Queen, who by all accounts was a brilliant performer, and because he wasn't seeking popularity or commercial profit, he could allow his imagination free flow.” Sudbin does not see these works as necessarily fixed by the limits of technique, instrument or musical creativity known to Scarlatti: “Both the Queen and Scarlatti were extraordinary harpsichordists and had great improvisational skills. It is very plausible that for each of the notated sonatas, there were 50 or so other versions.” He later speculates that due to the diversity of the sonatas, their immense creativity, that Scarlatti had an inkling that a better instrument (the modern piano) would exist in the future, and that musical styles would continue to evolve. The last two points are a defense to suggest that Scarlatti would not have been surprised to hear his works played differently as time moved on. So Sudbin allows himself certain luxuries in his interpretations. He utilizes the binary form that Scarlatti composed in to play the material once through largely as one would expect. The A section in K. 159 is unoffending the first time through but with an immense and joyful character: brassy fanfare in the right hand and a dancing lilt in the left. But listen to what he does in the repeat! The opening is played softly and with the pedal for the first 4 measures, before contrasting with the fanfare texture the next 4 measures. The next two phrases continue this trade off. No student could get away with this muddy texture because it’s not traditional. “Scarlatti didn’t have the damper pedal!” But it makes sense. Sudbin still has clarity, he’s just opening up the strings of the piano to vibrate more openly as the strings on a harpsichord (which doesn’t have dampening at all) would. It’s a color, not an obfuscation of the texture. He also allows himself all kinds of ornamentation upon the repetition (as he does in his Haydn recordings). Improvisation, afterall, was an essential part of one’s musicianship during the time that Scarlatti wrote, and one can easily argue that for any composer from the 18th, even 19th centuries, what is on the page need not be a limit to what one does in performance (you could even hear his liberal use of the damper pedal as simply an ornamentation). In the fourth system of the first page (I’m looking at this score), a leaping motive is enlarged to over an octave. For the last one, jumping up to D, he ornaments the approach with a glissando, adding to the spritely spirit. On the second page, in the second system, he holds the low Gs, perhaps with the sostenuto pedal, then reorchestrates the parts. Both parts as written are taken in his left hand, and the right hand doubles the melody an octave higher. He treats the piano momentarily like an organ as pedal stops, different manuals and octave coupling create a variety of color. He adds simple ornaments, trills, appoggiaturas and doubling octaves. But he goes as far as to add notes. He fills out the bare octaves at the very end of the pieces with an ornamented third. Not a big deal, except ending on open octaves is a common thread in Scarlatti’s music. All of these changes are just a gateway into understanding the beautiful artistry Sudbin brings to Scarlatti’s music. Each one sounds like the work of a different composer, and each individual sonata is full of variety. Listen for his ever evolving variety of articulation, ornamentation, or sudden surprises in the left hand voicing, etc. While K. 159 is a fanfare, K. 208 is a dramatic operatic aria and K. 213 in d minor is a dark lament. Sudbin plays both the famous and the obscure sonatas with an equal admiration and careful crafting to show the ingenuity, virtuosity and artistry of Scarlatti. **This post contains affiliate links. While I may receive a small compensation if you purchase any of the products mentioned, the words used to promote them are completely genuine and offered regardless of any personal earnings**

She concertized as a young woman around Europe, but settled to raise a family, continuing performing during World War II. Moving to the U.S.A. after the war, she never gained a significant performing career, even though at her age she still played with impeccable technique and musicianship. The recordings we do have from her exist from this late part of her life. (See this website for my sources, and more, on this incredible life story.) Typically I believe in supporting artists by, at the very least, streaming their recordings from legitimate services like Spotify or Apple Music. Unfortunately, most of Freund’s recorded work is unavailable anywhere, even secondhand CDs. YouTube is the best way to make her art visible. I’d like to continue my focus on Brahms. Seeing as how he adored Freund’s playing, it is noteworthy to hear her approach to his music. What old performance practices, perhaps things decried today as outlandish techniques, do we hear from this legitimate, audible record of the composer’s intentions? To see, let’s briefly walk through just the first movement of Brahms Sonata No. 3 in f minor, Op. 5. My hope is that illuminating some of the techniques in her performance will give you a greater appreciation for her extraordinary intentions in music making. This is quite a different approach than I took in the first post about Glenn Gould! I’d recommend listening to the first movement in its entirety with the score, read my post and check out the specific spots, then take some time to listen to the Sonata in its entirety, perhaps without the score. You’re in for a treat! Significantly, throughout the performance, we hear plenty of unmarked arpeggiation of chords, or anticipation of the left hand. These unmarked forms of subtle rubato are so common amongst early recordings by pianists trained in the 19th century and are so often vilified as ‘sentimental’ today. You can’t perform asynchronously what is marked to be played synchronized! And yet, they do. Consider measure 7, (hear it here). Asynchronization of the hands is tricky to hear, so much that you probably need headphones on to hear it properly, but the left hand is slightly agitated, often anticipating the right. You’ll also hear this technique in nearly every lyrical area. Consider the second theme in the first movement (measure 39). The left and right hands are so asynchronized that one would almost hear this as Chopin. Often times these techniques are closely related to polyphonic playing. Pianists create more layers by arpeggiating or asynchronizing the hands, allowing our ears to catch up to hear melodic lines that we otherwise would not be aware of. In doing so, the harmonic structure and natural counterpoint is laid so much to the fore. Freund is incredibly sensitive to the polyphony Brahms himself wrote in. Consider the c# minor section of the development (heard hear). Each voice is matched perfectly to itself, and balanced with each other so that the canon is easily audible. At the same time, the general harmony of the phrase has drive and direction. Contrast that with the searching melody which happens at the key change to 5 flats. The syncopated right hand chords are played as triplets, rather than eighth notes but this lilt provides rhythmic anticipation which suggests the harmonic stability is an illusion, pointing us towards the true, unstable, development which will break out momentarily. Consider her tempo. The first movement begins at a quarter note around 70. The second theme is actually played faster, beginning in the 80s and accelerating (even before the un poco accel) to the 100s. I’ve heard it argued that all tempos in such classically minded composers must “live under the same roof”, that is, to be very closely related to each other, considering that they share the same foundation. I’ve also heard it argued “you don’t feel the same in the living room the same way you do in the kitchen or bathroom!” Freund, and pianists of her generation seem to feel closer to the latter: themes have their natural tempo which must be taken to promote the true character. The un poco accel at the ended of the exposition are treated as significant events, there’s nothing ‘little’ about them! Furthermore, they are more a sudden change of tempo, rather than gradual. But she slows down significantly for the cadences, especially the final resolution on the repeated Db major chords. She’s extremely mindful of the structural significance of every measure she plays. Listen to the last 23 measures (heard here). This is the first theme heard in the parallel major, and the tempo is just a little faster than the opening of the movement, mid-80 beats per minute. The Piu Animato jumps to nearly 100 beats per minute, which is fair enough. But the hemiola section 5 measures later is suddenly at 170, without provocation. Would you have noticed that if I didn’t point it out to you? I’d wager you wouldn’t, and that’s the key. Unless you’re counting along with a metronome like I was (for analysis purposes!), you aren’t consciously aware of these vast changes of tempo. Our primary focus ought to be on the transformative artistic picture which she is creating. The tension her changes of tempo create are more important than the means used to create the tension. I’d like to point out one more minor detail which sets mature artists apart from mortals like myself. In the development, 8 measures before the key signature returns to 4 flats, the left hand begins with a dotted sixteenth, 2 thirty-second note rhythm (heard here). She voices the thirty-second notes very clearly, instead of throwing them away. In fact, it’s almost like the first short note has a slight accent, which typically is a big no-no. But she has a specific reason for paying attention to these short notes: in the fifth measure of this motive, the thirty-second notes are followed by an eighth note, jumping up a tenth. Given her attention to the short notes preceding, we can hear the stretch of that interval. It sounds like one voice, where as so often, this motive sounds pointilistic, like two different instruments, which given Brahms’s phrase marking, is not the intention. On a closing note-there are several other Etelka Freund performances out there, other Brahms and a few other composers including Bach, Lizst and Bartok. Check them out. They all sound like Etelka Freund, which is a mighty fine accomplishment. If we inevitably are influenced by music around us, as I will always argue, we’re never going to present a sound authentic to only the composer. Rather than sounding like a neutered version of someone else’s impression of the composer, we might as well make an intentional effort to sound most consistently like ourselves.

Chopin is a composer ultimately focused on sound and poetry. Gould is a performer ultimately focused on structure.

In this latter approach, the composer doesn’t matter so much as the construction of the piece. How the notes were put together mattered more than the sounds they made, perhaps in the same way that a building would be judged whether it was functional, not how it looked. Says Kevin Bazzana in his book Glenn Gould: The Performer in the Work, ““Gould was concerned with musical expression but was motivated by musical structure.” (page 13, first emphasis mine, second in the original) The function could be innovative, but only because the structure first and foremost, was. Bazzana quotes fellow Bach specialist Rosalyn Tureck as saying: “In Bach’s music, the form and structure is of so abstract a nature on every level that it is not dependent on its costume of sonorities. Insistence on the employment of (period instruments) reduces the work of so universal a genius to a period piece…In Bach everything that the music is comes first, the sonorities are an accessory.” (page 21). This universality is essential, I think, to understanding Glenn Gould’s performance. It is a universality which truly opens the performer up to playing with extreme sensitivity to musicality and expression that’s inherent in the work. That sensitivity may not be inherent in the standard practice of a piece, thus we get to hear Gould’s unique style of playing (see his recording of Beethoven’s final 3 Piano Sonatas for an example of something strange that, I believe, ‘works’). So Gould, “could ‘let loose’ in performance only with music whose structure met his standards of idealism and logic, music that he could first justify rationally.” (page 35) Chopin, not focused on structure will never sound truly revelatory and natural in someone like Gould’s hands. And that brings us to Brahms. Glenn Gould recorded 10 Brahms Intermezzi early in his career, in 1960. (Later in his career, indeed one of his last recordings, he also recorded the Op. 10 Ballades and the Op. 79 Rhapsodies). These Intermezzi, I do believe, constitute the most perfect musical recordings in existence, and they are often overlooked in Gould’s output. At first, Brahms seems not the quintessential Gould composer, especially given his controversial performance with Leonard Bernstein of the first concerto. But when we remember Brahms’s classicist bent, his love of Bach and Renaissance polyphony, his dedication to absolute music, it makes sense. These short forms (as opposed to the earlier Brahms Sonatas and Variations which Gould decried as “pianist’s music”) fit his temperament perfectly. On these pieces Gould himself says, “I have captured, I think, an atmosphere of improvisation which I don’t believe has ever been represented in Brahms recordings before…total introversion, with brief outbursts of searing pain culminating in long stretches of muted grief…” Or, in his words, these are the ‘sexiest’ recordings ever made (these quotes from the liner notes of this other volume of the recordings). Call it sexy or not, the Intermezzi are performed with incredible attention to expression of the melodic line, harmonic shaping, rubato and structural drama. Given the way he shapes and connects melodies or layers the polyphony, I truly believe that Gould could hear with better detail than a typical musician. Like Gould’s Bach, every line in these pieces sounds independent and musical. I point your attention to the counter melody on the repeat in the B-section of Op. 118 no. 2 and when the melody returns in the minor a few phrases later. I hesitate to analyze much further because of the perfection I hear, these recordings just speak for themselves. He has a way of balancing different lines to make us listen to something different every few measures, without losing what we were listening to before. He magically forces us to listen polyphonically. Clearly Gould was not a dry, mechanical performer, but was capable of intense romanticism in his playing. We hear it clearly in these Brahms recordings, evidently just because by looking at the structure first, he could see the beauty inside the functional, rational architecture that he simply doesn’t see when the elements are reversed in something like Chopin. A lot of studying the piano is learning to copy, from our youngest years through at least until completing undergraduate education. Initially, this isn’t a bad thing. We need models to learn:

But there comes a time that we want to move away from copying. Until we do, we generally only function as accidental, or perhaps unintentional, pianists. We’ve done everything by chance, regurgitating what we’ve learned instead of processing and adding value to everything we’ve been taught. Sometimes when we think we’ve gone off on our own, we haven’t actually done so. I’ve argued that the act of performing is at least as important as the texts on which our performances are derived. I believe our ears are easily manipulated by what we hear and most of our performance decisions are not truly our own; see case studies in Beethoven and Liszt. And so I’d like to suggest embracing what I have decided to call 'intentional pianism'. What makes a great pianist stand out? Our favorite pianists have at once a pianistic voice that is all their own, that sounds completely familiar, and simultaneously keeps us thinking and guessing. They’ve studied all the rules but have commanded the authority to break them. They have a sort of intentionality to the way they play music. All this is not to suggest that intentional piano playing is limited to the great masters. Some of my absolute favorite musical memories are from pianists who are not famous to the general classical music population. Some of the most distinctive performances I’ve seen were by students who brought an energetic commitment rare among artists, others are from professional artists who have sought their own career path, whether to pursue unique repertoire or venues for their performances. Anyone can play with intentionality. Nor do I want to suggest that our educational system is failing students. I’ve benefited from studying with an incredible, diverse group of piano teachers, all of whom are brilliant, and largely fall into the category of a ‘traditional’ piano teacher. And there’s nothing wrong with role of traditional piano teacher, in fact, traditions are essential. But to step out as performers with a personal intentionality, we need to use traditions as a stepping stone, not an end in themselves. Our professors in lessons and classes only have so much time to help us reach the level of being a unique artist. My goal with this blog and other future endeavors is to supplement the great teaching that goes on in piano lessons and schools of music. I believe some of the keys to being intentional include:

With this blog, most of all, I hope to outline how one can become a truly independent, a truly intentional pianist. Over the course of this next year, I’m going to present 5 blog series along with several standalone posts. First will be Extraordinary Recordings, a series studying several of my personal favorite performances on record, focusing on what makes the performer so unique. This will be, in a sense, a series of 9 case studies on pianistic intentions. Simultaneously, I will report on my viewing of the Cliburn Piano Competition, my favorite performances as well as thoughts on the repertoire chosen, and nature of competitions in general. What better way to ruminate on the state of intentionality than by studying this competition of world-class, young talent? Later on, with the hope of inspiring some summer reading, I will release a series of posts on Influential Books. Some of these will be explicitly musical, but several will be from outside the musical world. In the fall, I will be ruminating on the Coexistence of Contemporary and Traditional Classical Music. This will be in preparation for a project that I’m very excited about, which I will announce later in the summer. Finally to end the year, I will discuss my views on Performance Practice, especially focusing on my work studying the amazing pianist Ervin Nyiregyhazi. I hope you’re as excited about this journey as I am. Please subscribe to my e-mail list to the right, as I would love to keep you apprised as each new series is rolled out, as well as my projects as a performer.

A change of pace from the Messiaen...

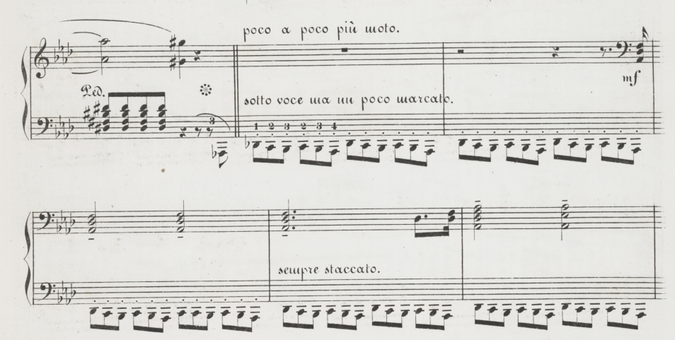

I have sat on this recording for almost a year and a half now. In general, I was not happy with this recording session and only had a couple movements of Mozart cleaned up to actually share publicly. But I’ve continued to think about this Franz Liszt run. It is messy in the beginning with a couple memory lapses but generally stays on track and presents how I’ve heard this piece in my head. But there is another reason I’ve always been hesitant to widely share my performances of this piece. I drastically depart from the standard performance practice in one notable area. Funérailles is famous for the middle section fanfare, the military parade which, as the route passes by the listener, the pianist explodes the thunderous bass ostinato with octaves. It’s virtuosic and may or may not reference Chopin’s famous A-flat Polonaise. Here’s the beginning of the section, from the first edition: Notice the tempo marking: poco a poco piú moto, or, ‘little by little more motion’ from the last tempo indication, which was adagio, in the very beginning. Other editions, including Henle’s Urtext, and editions by Emil von Sauer and Liszt student Jose Vianna da Motta agree. And YET no one plays it like this. At the beginning of this section, the second measure in the excerpt above, performers always take a new, fast, tempo. I’ve never understood this. Franz Liszt clearly marks a new tempo (Allegro energico assai) only at the climax of this section, and continues to reinforce the poco a poco piú moto until that point is reached. But performers always begin this section very fast. Are they afraid that they will not be fast enough by the time octaves are introduced and be accused of lackluster octave technique? Practice pacing yourself. You can start slowly but get to a tempo to leave no doubt in your abilities. You run the risk of the opposite problem: starting fast, and trying to get faster so that your octaves are doomed to fail. Even Horowitz succumbed to this extravagant failure and had to drastically cut the tempo back at the climax of the section. My performance of the military march here is an accurate depiction of this section, I think, and the effect of movement, the tension of the unyielding ostinato, and the pride of the moment is accentuated if this section begins adagio. It makes for a strong musical choice, but I have yet to find anyone to actually make this observation, whether in writing or in performance. Particularly listen to 7:00-9:15. The military march section begins at 7:25, the octaves at 8:30, and the Allegro energico assai at 8:50. What do you think? Give it a couple listens then tell me if you're convinced, or if you find the sudden tempo change a better choice. I'd love to hear from you! In my undergraduate piano literature class covering Baroque music, one of our assignments for the listening exam was to study 4 recordings by different pianists of Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in E major from Book 2 of the Well-Tempered Clavier such that we could blindly identify the pianist. I remember two of the pianists were Edwin Fischer and Glenn Gould, and whoever the other two were, they continued the trend of reasonable interpretive distinctiveness. I was fascinated to compare and contrast these different performances, and found the assignment manageable but learned more by studying the recordings with classmates who had much difficulty distinguishing the performers. So often we listen to the work, how often do we listen to the performers?

I think this is one of the greatest deficiencies of advanced musical study today: we spend so much time talking about great composers that we rarely talk about great performers. Academically, we ask what makes composers great, distinctive, creative? We really only ask the same thing of performers obliquely by talking of ticket sales, numbers of commercial recordings, and who is the most exciting to watch live. Rare is it to see performance of canonical literature treated to an academic analysis, as if music need only be between a composer and the audience. In large part I’d hazard that this is due to the focus in teaching performers on the “composer’s intentions”. Interpretation is an act of properly conveying notational symbols in the score with sound. I don’t buy that, and I fall more in line with the Richard Taruskin quote to the right when I’m studying a piece and preparing it for performance. This is a common theme in my thinking, and my own academic work (and thus, why I’ve titled this blog “Performer’s Intentions”). As a pianist, I am an intrinsic part of the musical circle, and while my musical decisions are based in the score, I’m not a slave to tradition because traditions are often wrong (as I will write about in future posts). I’ve just begun working on Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. Since this work is commonly heard, I’ve decided to inundate myself with different recordings, to see the variety of approaches pianists have taken. There are many similarities, so many performers today painstakingly playing the sometimes awkward or unnecessary passagework that the non-pianist Mussorgsky wrote. There’s some virtue there, but there’s also virtue in finding new solutions to convey the musical work. There’s a fantastic recording my Maria Yudina, someone with an appropriate musical lineage and geographic authority to be taken seriously. One of my favorite tricks that she uses is inserting a glissando into the Baba-Yaga movement (measure 74, or hear it here). The grace-notes written are a physical nuisance to play, why not amplify the effect while making it easier? Continue listening through the rest of her recording: her ability to manipulate time is highly dramatic and effective. This blog title is certainly to be taken tongue-in-cheek. I don’t hate music but what I do hate—and what I think the Bernstein song that inspired the title was getting at—is the culture of what classical music has become. Stuffy concert-halls, egotistical performers, interpretations that must follow a standardized formula based on modernly-conceived “rules” of tradition. I hope to explore many of the contentions I have with the classical music world through this blog. I did not begin to truly enjoy music until just a couple years ago. There are only a couple books that have changed my life: the Bible, Stephen Covey’s “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, William Westney’s “The Perfect Wrong Note” and Kenneth Hamilton’s “After the Golden Age”. The last I read over Christmas break in the first year of my master’s degree and found it such a relief. I will surely talk about it a great deal later so suffice to say now: it addressed a side of making music that was lost in the 20th century. It inspired me to listen to the oldest recordings of pianists who studied in the 19th century. We have on record performances by people who were trained in the musical style of the time in which the great piano canon was created. These recordings sound bizarre but here are the performance practice of Liszt and of Chopin, of Brahms and Schumann, even of Mozart and Beethoven. And yet it is not the performance practice propagated by performers today, whether or not they claim to be authentic interpreters. Music was openly subjective back in “the day”. Says Richard Taruskin (another hero of mine, though he certainly goes over the top on occasion, and his repulsion towards contemporary music is alarming) regarding music as museums and performers as curators: “In musical performance, neither what is removed nor what remains can be said to possess an objective ontological existence akin to that of dust or picture. Both what is ‘stripped’ and what is ‘bared’ are acts and both are interpretations—unless you can conceive of a performance, say, that has no tempo, or one that has no volume or tone color. For any tempo presupposes choice of tempo, any volume choice of volume, and choice is interpretation.” (Texts and Acts, page 150). I have arrived at the point that anything claiming to be music is worth a listen. Popular, classical, why must we even make the distinction? I believe to tout the genius of composers of the past, or the inerrancy of a musical score is to do a severe disservice to our art and the satisfaction we can get out of performing that art. I used to be more close-minded, in music and all walks of life. I knew what I believed, that I was ‘right’ and I arrogantly defended my positions. Just a few years ago I would have openly shot down my two great music loves: Liszt and contemporary music. Now I could be satisfied playing both, or either, for the rest of my life. Music—in the most subjective and therefore true sense—should never be boring and it should always throw you for a loop once in a while. Final thoughts go to Alex Ross in a great article in the New Yorker from a few years ago: “Music is too personal a medium to support an absolute hierarchy of values. The best music is music that persuades us that there is no other music in the world. This morning, for me, it was Sibelius’s Fifth; late last night, Dylan’s ‘Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands’; tomorrow, it may be something entirely new. I can’t rank my favorite music any more than I can rank my memories. Yet some discerning souls believe that the music should be marketed as a luxury good, one that supplants an inferior popular product. They say, in effect, ‘The music you love is trash. Listen instead to our great, arty music.’ They gesture toward the heavens, but they speak the language of high-end real estate. They are making little headway with the unconverted because they have forgotten to define the music as something worth loving. If it is worth loving, it must be great; no more need be said.” |

"Modern performers seem to regard their performances as texts rather than acts, and to prepare for them with the same goal as present-day textual editors: to clear away accretions. Not that this is not a laudable and necessary step; but what is an ultimate step for an editor should be only a first step for a performer, as the very temporal relationship between the functions of editing and performing already suggests." -Richard Taruskin, Text and Act Archives

March 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed